North Vancouver City Library Adult book club October book

Excerpts

Equally crucial is the need to revisit and re-embrace the teachings of the Ancestors, collectively, in this country—all of us. This seems even more relevant today as we witness seriously tumultuous times around the world. Love should be honoured always, respect should be upheld unconditionally, courage should not be a response to fear but a bold empathy for others. Honesty must become the underlying principle of our relations, lessons of our mutual past the national trait of our collective wisdom, humility our constitutional ethos, and truth our path henceforth.

No Reconciliation in the Absence of Truth and Justice

ROMEO SAGANASH

Former Member of Parliament & Jurist

CYNDY: Teaching in circle, circular classrooms, land-based classes, courses taught in community, more Indigenous professors, and learning from their entire being will be available to all students. Education will then be based on “two-eyed seeing,” a concept that Mi’kmaq Elders Albert and Murdena Marshal coined, encouraging learners to see from one eye with Indigenous ways of knowing and from the other eye with mainstream ways of knowing and, importantly, learning to see with both eyes together—for the benefit of all.17 Indigenous youth will settle for nothing less.

Our Future Is Young, Educated and Relational

MINADOO MAKWA BASKIN

Student & Leader

and

DR. CYNDY BASKIN Writer, Researcher & Educator

17 C. Bartlett, C., Murdena Marshall and Albert Marshall, “Two-Eyed Seeing and Other Lessons Learned within a Co-learning Journey of Bringing Together Indigenous and Mainstream Knowledges and Ways of Knowing,” Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 2 (2012) 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-012-0086-8.

CYNDY: Innovative approaches will ensure that students have opportunities to be out in nature to learn about the rivers, the land and the kinship one can acquire by being on and with the land. Elders and Knowledge Holders will do activities with them out on the land. Other educators will help relate Indigenous knowledges to science, math, reading and physical activities. Education will be holistic and integrated. Again, in keeping with Indigenous world views, another advocate of twenty-first century education, has written about the need to educate for the future of the planet, with an emphasis on responsible local and global citizenship, sustainable economics, living within ecological/natural laws and principles, the inclusion of multiple perspectives, and a sense of place.16

Our Future Is Young, Educated and Relational

MINADOO MAKWA BASKIN

Student & Leader

and

DR. CYNDY BASKIN Writer, Researcher & Educator

16 J.P. Cloud, “Educating for a Sustainable Future,” in Curriculum 21: Essential Education for a Changing World, ed. H.H. Jacobs (Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2010), 168– 185.

CYNDY: Thus, in the future, education will be more about understanding than simply receiving information. It will be about wanting to understand the world, rather than controlling it. Individuality will be revealed as the myth it is because nothing is ever done by only one person. Learning will be accompanied by a focus on resiliency and how to sustain positive mental health. Children and youth will be investing more time in revealing their biases and becoming more critical of the sources of information provided to them. Hence, they will learn how to investigate and verify what they are being taught and who is teaching it to them. They will be more in tune with their bodies and the mental reactions they have to people and occurrences around them because their education will include learning how to meditate. This will lead to a greater understanding of themselves as connected with everyone and everything else. When they know these things and can see how their minds work, it will be “the first step toward ceasing to generate more suffering” in themselves and the world around them.5 It will also avert the algorithms making up their minds for them (LOL)!6

Our Future Is Young, Educated and Relational

MINADOO MAKWA BASKIN

Student & Leader

and

DR. CYNDY BASKIN Writer, Researcher & Educator

5 Yuval Noah Harari, 21 Lessons for the 21st Century (Toronto: Penguin Random House Canada,

2018), 318.

6 Harari, 21 Lessons.

MAKWA: Anishinaabe protection of the land, or Mashkikiiaki’ing, teaches us that there are no natural disasters. Everything has a cause and effect, as we are all related to one another in the four directions associated with the medicine wheel. This much has been realized, but the preventive work to combat negative outcomes as prophesied may not be done until the earth nears its cosmic end. In Indigenous fashion, as we experience situations resembling an end, in the future, we as a people, will experience a new relationship with the ancestors, where hopefully we can all be guided to a path of mino-pimâtisiwin, the good life. But to do so, the Elders have said that we must isolate on the land and cultivate our medicines, a double entendre, I am sure, meaning we must research the medicinal plants but also look inward to find our roots as medicine people.

Our Future Is Young, Educated and Relational

MINADOO MAKWA BASKIN

Student & Leader

and

DR. CYNDY BASKIN Writer, Researcher & Educator

Water is the giver of life, and I’ve always been drawn to it—sought to live in a place where a lake, river or sea is visible or, even better, both visible and audible. My mother used to say that I was conceived on the banks of the Nechako River, and in my late twenties, life’s circumstances brought me back to that place, like the salmon of that river system returning to its place of creation to spawn (except I didn’t have the good fortune to do that there). I may have been conceived on the banks of the Nechako, but I was born in the neighbouring watershed, near the Athabasca River, and raised along the Salteaux, Slave, Athabasca and Makhabn (Bow) Rivers. I have lived on the shores of Stuart Lake, Shuswap Lake and now the Salish Sea. Without these bodies of water, I would be nothing. They’ve comforted me, nourished me and inspired me, and they continue to. I was never taught this, but wherever I go, intuitively, I pay homage to the nearby bodies of water, and this brings me great satisfaction and peace, and also seems to strike a chord with those who are present as witnesses.

Me Tomorrow—Paint It Red

DARREL J. MCLEOD

Writer, Educator & Activist

In the late 1980s, when I was a school principal in Yekooche First Nation in northern BC, I intuitively had insight into the importance of ecosystems. In establishing the curriculum for the school, I scrapped the government-prescribed program of studies to instead focus on local knowledge—to help the students learn about the ecosystem they were heirs to, the one they would one day, as adults, become the stewards of. We mapped the streams, rivers and lakes within the territory and then beyond to show how their ecosystem connected with others. With the Elders and other adults of the community, we explored how that ecosystem has provided sustenance for the people of Yekooche since the beginning of time, and we explored the traditional names of the lakes, streams and rivers in the local ecosystem. I believe it was during my time with the Yekooche people that I came to appreciate the sacredness of bodies of water and their importance to human survival and sustenance. Whenever I mention a river or lake in my writing now, I strive to find and use the Indigenous name for it.

This returning to the Indigenous names of bodies of water and landmarks is critical in the process ofrepudiating government ownership and title over these bodies of water (and their beds and shorelines), and of renewing or continuing our role as stewards and protectors of the ecosystem(s) within our territories.

Me Tomorrow—Paint It Red

DARREL J. MCLEOD

Writer, Educator & Activist

In the 1990s, in an amazingly beautiful part of Nuu-chah-nulth territory called Clayoquot Sound on the west coast of Canada, there was an intense conflict between industry, government and the local First Nations (and their allies) related to the logging of an old-growth forest. Hoping to find a solution to the stalemate, the provincial government of BC decided to convene what it called the Clayoquot Sound Scientific Panel. On this panel, Nuu-chah-nulth Elders were given the same standing as PhD-level scientists. After months of working together, the Elders and scientists gained tremendous respect for each other, and together over the course of a few years they concluded that an ecosystem approach to environmental management was the only sustainable method possible. To this day, I am not aware of such a progressive body being established anywhere else, a body in which Western scientific knowledge is paired with Indigenous knowledge to design a sustainable approach to environmental management. Indigenous people will increasingly demand that their knowledge be given standing equal to the so-called scientific knowledge of Western society, as occurred in this situation. And, increasingly, scientists will validate that knowledge.

Me Tomorrow—Paint It Red

DARREL J. MCLEOD

Writer, Educator & Activist

The disruption caused by generations of families attending residential school has caused a great chill in the parent-child relationship in Indigenous families, and increasingly natural human warmth and instinctual love is already healing this issue and will continue to do so. The healing power and warmth of fire will help to address the suicide crisis mentioned earlier. Multi-generational trauma takes decades to heal, but within the next twenty to fifty years, more healing will occur and Indigenous Peoples around the world will thrive.

Me Tomorrow—Paint It Red

DARREL J. MCLEOD

Writer, Educator & Activist

Since time immemorial, the earth has provided us with all that we need to flourish as Indigenous people and live long and healthy lives. Young Indigenous scientists are exploring elements of our traditional diet that are missing in the present day and are bringing back traditional food sources that will help us to combat conditions like diabetes, obesity and mental illness… In addition to nutrition, the earth also provides us with medicines we need to maintain and enhance our physical and spiritual well-being. Indigenous Peoples all over the world have ancient knowledge of the plant and animal parts used in these medicines. The resurgence we’re seeing in the use of our medicines will continue and expand, as will the borrowing of this important part of our culture by the mainstream.

Me Tomorrow—Paint It Red

DARREL J. MCLEOD

Writer, Educator & Activist

Mother Earth—the Pachamama—is everything to Indigenous Peoples. She does not belong to us; rather, we belong to her, and how our relationship with her evolves will determine our future. Over generations, the acculturation by dominating forces has eroded our direct and innate connection with Mother Earth to the point that many of us find ourselves quite removed, literally and/or figuratively, from our place of origin, sometimes feeling like we’re in a true physical exile or simply forced to live and strive somewhere else, away, for the sake of survival and expediency. Increasingly, Indigenous people will re- establish the connection with our places of origin, our original birthplaces—the land, water, air and fire there—and make our presence known. We will ensure that our cosmovision is known to our youth, and they, in turn, strengthened and emboldened, will change the world—for the better.

Me Tomorrow—Paint It Red

DARREL J. MCLEOD

Writer, Educator & Activist

The future of humankind lies waiting for those who will come to understand their

Vine Deloria Jr., God Is Red

lives and take up responsibilities to all living things. Who will listen to the trees,

the animals and birds, the voices of the places of the land? As the long-forgotten

peoples of respective continents rise and begin to reclaim their ancient heritage,

they will discover the meaning of the land of their ancestors. That is when the

invaders of the North American continent will finally discover that for this land, God is red.

OUR GENESIS TELLS us we are Sky People, the Ǫ:gwehǫ:weh. It is nice to read and hear that science is just now catching up with our Genesis through their big bang theory.

Me Tomorrow: The Journey Begins . . .

I am so glad that words such as death, dead and died are insults in our languages. We can say those words in our languages too, but it demeans the person’s stature. We prefer instead the phrases Aǫdawihshęh (they are resting now) or Asǫngihędęhs (they went on ahead of us). These phrases, emanating from our Cayuga Language, are so beautiful. They tell us that in our transcendence, the moment we return to the Sky World, or O:węja ǫweh, we will move along a path covered in strawberries, with the air saturated with their aroma.

TAE:HOWĘHS, AKA AMOS KEY JR. A ROYAL MOHAWK

Educator & Advocate

If one were given a certain amount of money to feed oneself for a year and told to use only this one particular store that sold unsuitable food, what would the options be? Make the case, take a stand and announce that another source must be used? What would be required to make that argument? One could say that another source provided healthy food that could be used now, plus seeds that could be sown to ensure food for tomorrow. This same argument could be used for developing curricula and localized, community-based education systems that are appropriate for our communities.

Our Education Tomorrow

SHELLEY KNOTT FIFE

Education Specialist & PhD Candidate

Indigenous people know this belonging, to the land, to this place, in the very heart of their being. The struggle has been to rise above the systemic efforts at work to eliminate this knowing. This struggle has involved retrieving the tools of our knowing. These tools originated where we thrived—in community, in extended family, on the land. A learning place of tomorrow would be an extension of that sense of place, surrounded by the family of community.

Our Education Tomorrow

SHELLEY KNOTT FIFE

Education Specialist & PhD Candidate

Real leadership knows that one needs to keep on reading, researching and learning. There is truth in the saying, “Leaders are readers.” I am also an avid reader of leadership and personal development books, as my personal library will show. One of the best leadership and personal development books (and training courses) is Steven Covey’s The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. Habit 2 is “Begin with the end in mind”—now that is seventh-generational thinking. And Habit 7, “Sharpen the saw,” is expressing and exercising all four dimensions of every human being—physical, social, spiritual and physical—regularly. Natives also talk of quadrants through the medicine wheel teachings—the physical, mental, emotional and spiritual—and the interconnectivity of all aspects of one’s being, including the connection with the natural world.

Seventh-Generational Thinking—Fact or Fiction?

CLARENCE LOUIE

Chief of Osoyoos Indian Band

i heard the singing through the fire

stones, trees, wind

and it helped me dreamso that today i may awake and sing, too,

for those yet to bei hope they will hear us one day

A’tukwewinu’k (storytellers)

calling out the stories

they will need to know and the songs to help them rise

SHALAN JOUDRY

Storyteller, Poet, Playwright & Ecologist

Each year, every child practises telling the story of their lineage and/or territory. As they age, they work on more details and going further back in time or more in-depth about their cultural histories. When they mix up the details or lose track, the adults assist, and the child revises the story in their mind. Each year, they grow their orality of their own history more clearly. On graduation from youth into adult life, they are invited to present who they are to the world, with only their memory to carry them. This means that at marriage ceremonies the full stories of the couple can be retold, as their individual lineages now merge.

A’tukwewinu’k (storytellers)

SHALAN JOUDRY

Storyteller, Poet, Playwright & Ecologist

I believe that oral storytelling is an elemental human tradition that will never completely pass away. I think it has just the same primal attraction as sitting around a campfire. I’ve worked with my partner, Frank, facilitating various workshops. It’s quite amazing that no matter the personalities or experience of the people sitting around that circle, if they are city people or camping people, or if they are Nova Scotians or from another country anywhere in the world, everyone feels attracted to the glow and movement of that fire. As if fire speaks to us, to the very depths of our humanity in ancestral memory. I wonder how many fires kept people alive through the millennia and all around the world. So, too, when we share a story and others listen in real time, in real space right in front of each other, our minds and hearts are triggered somewhere deep and anciently human. Oral storytelling must be as old as humans. Stories have been used as teaching mechanisms, for entertainment, for ceremony and much more.

A’tukwewinu’k (storytellers)

SHALAN JOUDRY

Storyteller, Poet, Playwright & Ecologist

We need nature. Many of us as Indigenous people speak about wanting to make sure that our young people still know how to survive off the land (just in case). No, more than just in case, we want them to know because it’s important to their spirit. As Indigenous people we recognize that having relationship with land, culture and traditional lifeways is more than survival—it makes us feel empowered and healthy. If our ancestors of long ago visioned forward to us now, i wonder if they would tell us that part of being a human is to be connected to the natural world and how that will never cease, no matter what kind of technology comes into the social realm.

A’tukwewinu’k (storytellers)

SHALAN JOUDRY

Storyteller, Poet, Playwright & Ecologist

We can learn many things from our mothers if we just take the time to listen and reflect. Every day was an opportunity to learn something new or old, or to try again. I’ve spent my years making sure I had something to offer my grandchildren. Just like I said in my speeches, many moons ago, as a youth activist.

In the Blink of an Eye

AUTUMN PELTIER

Age 17, Activist & Water Rights Advocate

It was a huge responsibility that we carried. She told me right from the creation story how I picked my parents and how my path was already made by the Creator. She told me how for nine months I lived in water, and how she kept her waters calm because she didn’t want to pass on intergenerational trauma. She told me how we got our first water teaching when we were in her waters. She told me how life can’t be made without water, as fetuses need water for development and survival. It is also where we learn unconditional love. And when the water breaks, like snow melting in the spring, new life comes. She told me as Anishinaabe-Kwe it is our role to nurture and teach the young girls. I remember her telling me of the importance of the berry fast and what it meant. Then that day came and I had to do mine. So many lessons were learned, but it wasn’t like reading a book, or Googling a ceremony—it was hands-on and it was our way of life.

In the Blink of an Eye

AUTUMN PELTIER

Age 17, Activist & Water Rights Advocate

When the Ancestors are calling and your spirit hears their calls, no matter what age you are, never ignore it. Follow your spirit. Trust your spirit and let it guide you. You never know where you will end up, what you will see, who you will meet, what you will learn. The experiences you will have when you trust your spirit and creator are endless.

In the Blink of an Eye

AUTUMN PELTIER

Age 17, Activist & Water Rights Advocate

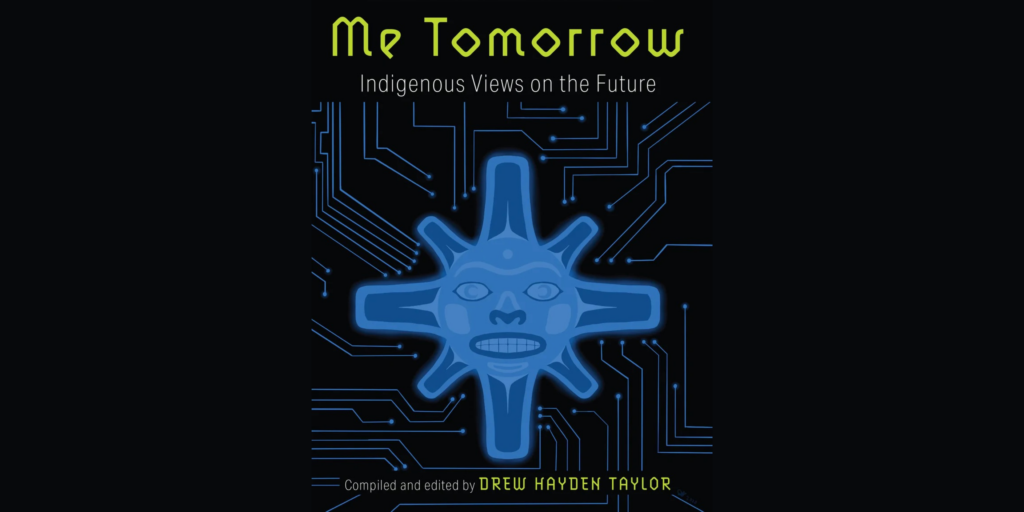

NVCL Book Club Reading Guide

Me Tomorrow: Indigenous Views on the Future compiled and edited by Drew Hayden Taylor

About the book: “First Nations, Métis and Inuit artists, activists, educators and writers, youth and elders come together to envision Indigenous futures in Canada and around the world.

Discussing everything from language renewal to sci-fi, this collection is a powerful and important expression of imagination rooted in social critique, cultural experience, traditional knowledge, activism and the multifaceted experiences of Indigenous people on Turtle Island.

For readers who want to imagine the future, and to cultivate a better one, Me Tomorrow is a journey through the visions generously offered by a diverse group of Indigenous thinkers.

Essays by: Autumn Peltier, Clarence Louie, Dr. Cyndy Baskin & Minadoo Makwa Baskin, Darrel J. McLeod, Drew Hayden Taylor, Lee Maracle, Dr. Norma Dunning, Raymond Yakeleya, Romeo Saganash, shalan joudry, Shelley Knott Fife, Tae:howęhs aka Amos Key Jr., Tracie Léost” [publisher].

About the editor: Drew Hayden Taylor is an award-winning playwright, novelist, scriptwriter and journalist. He was born and raised on the Curve Lake First Nation in Central Ontario. Taylor has authored nearly thirty books, including The Night Wander: A Native Gothic Novel (Annick, 2007) about an Anishinaabe vampire. He also edited Me Funny, Me Sexy and Me Artsy (Douglas & McIntyre, 2006, 2008 and 2015), and has been nominated for two Governor General’s Awards. He lives in Toronto.

Interviews and articles:

- Ottawa International Writers Festival: “Me Tomorrow: Indigenous Views on the Future with Drew Hayden Taylor, Norma Dunning and Darrel J. McLeod”

- CBC Day 6: “Indigenous writers paint picture of hopeful future in new essay collection”

- CBC Unreserved: “From growing medicine to space rockets: What is Indigenous futurism?”

- University of Alberta Library: “Indigenous Futurism” – links to interviews and further reading on the subject

Discussion Questions:

1. The philosophy of the Seventh Generation is mentioned in several essays. What do the authors say about it, and how does it influence their specific thoughts on the future?

- Actions have consequences

- Thinking of humans that are dealing with the consequences

- It’s a very long time frame

- Affects not just human life, but thinking not his scale

- Non-linear, going back generations to the past and to the future. It is all connected

2. How do you see what might be considered traditional or ancestral Indigenous knowledge woven with visions of the future in these essays?

- Two-eyed seeing. Seeing with indigenous and western eyes

- Oral storytelling. Sitting around a fire and being able to connect through the spoken word.

- Reclaim the tradition of knowing where we come from. The story of our peoples and our ancestors and how important it is in our identity and having a foundation of the future.

- Humans tell stories from one generation to another.

- Storytelling as a way to impart wisdom

- Respect for elders and learning from them

- Respect for those who came before

- Preserving wisdom and knowledge through the care for elders

3. Hope is a central component to many of the essays in this collection. Where did you see the concept of hope appearing in these works?

- Hope is important but not useful when it’s empty

- Real hope and how it can become a reality

- Practical action

- Hope important for moving from the pain of the past into the present and future

4. What other emotions did the authors express through their writing? What would you say is the most prevalent emotion throughout the book?

- Feeling of “we’re being heard finally”

- Feeling more empowered to speak and be listened

5. How does this book compare to other works of Indigenous history, culture, and current affairs that you’ve read? How did these essays about Indigenous futures help you learn about the past?

- Perspective from indigenous writers versus the folklore through white/western lens

- It’s not all in the past, but also hopes and dreams for the future

- Rebirth of the seven generations

6. How does Me Tomorrow challenge stereotypical views of Indigenous people?

- Reading something like this would be more representative versus a lot of stereotypes portrayed

- We all need to appreciate the richness of indigenous cultures by listening to their voices instead of what dark images portrayed by media

- Indigenous peoples are still alive and here, not “dead Indian” like Thomas King jokes in the Inconvenient Indian.

- Demolish the idea of victimhood and are stepping up to the challenge of forging a future

7. The book features essays from writers of all ages and a wide range of backgrounds: educators, politicians, writers, students, activists. Did you like the variety of issues that the writers covered? Are there other topics that you would’ve liked the book to address?

- Reparations and more specifically what is “land back” and what is meaningful progress to reaching that

8. Is there anything particular from the book (a passage, argument, etc.) that challenged you, or that you didn’t enjoy? Please be specific and constructive with your thoughts.

- Water is the giver of life, and I’ve always been drawn to it—sought to live in a place where a lake, river or sea is visible or, even better, both visible and audible.

9. In his essay, Drew Hayden Taylor writes about the science-fiction genre and its relation to Indigenous culture and storytelling. What are some of the common depictions of the future that ‘classic’ sci-fi often depicts? How do they differ from Indigenous views of the future (particularly those in Indigenous sci-fi, if you’ve read any)?

10. The text at the top of the front cover reads: “An unraveling of linear time—Indigenous Futurisms seek not only to imagine Indigenous life years into the future, but to contest chronological colonial visions of time—a deconstruction, and envisioning, a summoning—Me Tomorrow constellates knowledge and invites discursive becoming, transforming the now so as to reveal what has been and what is to come.” Did you find that any of the essays addressed the notion of non-linear time, or any other themes presented in that quote?

- Everything has en effect on each other

- Cyclical

- Infinity symbol

11. Did one (or more) of the essays stand out to you the most? How come?

- Autumn Peltier, creating the life in the future as a 17 year old

12. Are there any lessons or inspirations from Me Tomorrow that you can take into your daily life?

- Importance of storytelling

- Respecting and learning from Elders

- Taking care of the planet

- Intergenerational healing

- Finding the Mother Tree – interaction and all things are connected. Ripple effects and ecosystems.

- The legends of the sky, and Indigenous tales actually echoing what modern thought called the Big Bang