I ka nānā no a ‘ike (By observing, one learns)

Kalahaku Overlook

The rim’s overlook, at 9,324 ft.

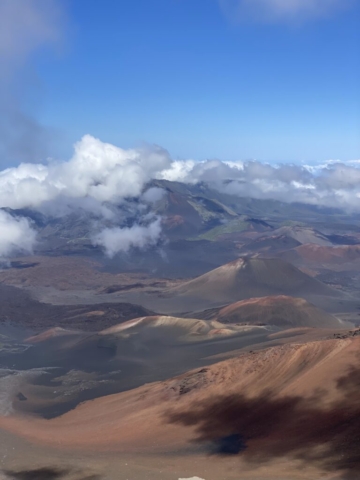

Pu’u Ulaula Summit (Red Hill)

Science City and the observatories are off-limits (kapu) to the public.

The parking lot is in the shallow crater of Puu Ulaula (Red Hill).

Haleakala’s highest point, Pu’u Ulaula Summit, offers extraordinary 360-degree views of Haleakala’s breathtaking landscape.

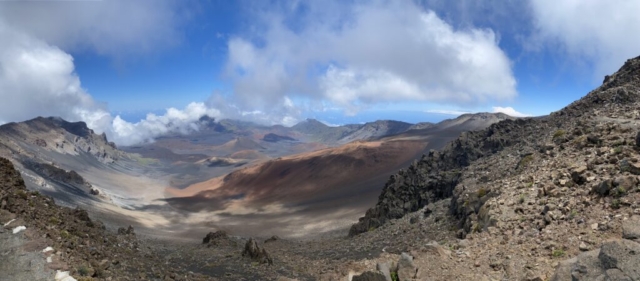

Haleakala Summit

Best views as the fog cleared for us to be able to see the crater and from this vantage begin to feel the scale of the place as hikers on the Sliding Sand Trail looked minuscule as they trek down deeper into the crater.

The overlook provides a panoramic view of the vast crater of Haleakala. This gigantic depression spreads 7.5 miles long (east to west), 2.5 miles wide, and 3,000 ft. deep. The entire island of Manhattan could fit inside the massive crater.

Leleiwi Overlook

The elevation here is around 8,800 ft.

The view from the crater lies exceptionally close to the moon. In the past, NASA used this area to view the moon. The astronauts who landed on the moon trained here.

Geology of Haleakalā

https://www.nps.gov/hale/learn/nature/geology-guide.htm

Plants of the Summit District

https://www.nps.gov/hale/learn/nature/plants-of-the-summit-district.htm

Birds of the Summit District

https://www.nps.gov/hale/learn/nature/birds-of-the-summit-district.htm

Behold, Hawaii

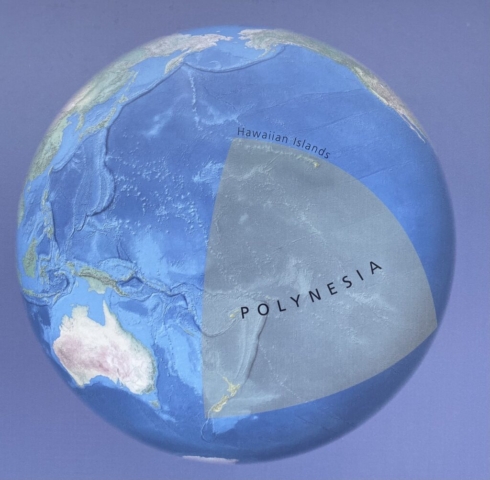

For millennia, Polynesian navigators explored the Pacific in large double-hulled canoes using stars, tides, currents, the wind, and patterns of bird migration. They introduced the concept of kuleana to malama ‘aina (the responsibility to care for the land).

We all share this kuleand and can respect the land by staying on trails, taking nothing, and leaving nothing behind.

Like Nowhere Else on Earth

Aloha!

Welcome to a place unlike any other.

Haleakala is home to a host of living things that arrived and thrived, against all odds, in the most isolated islands on the planet.

Today, Haleakala protects the last or only home for plants and animals found nowhere else on Earth.

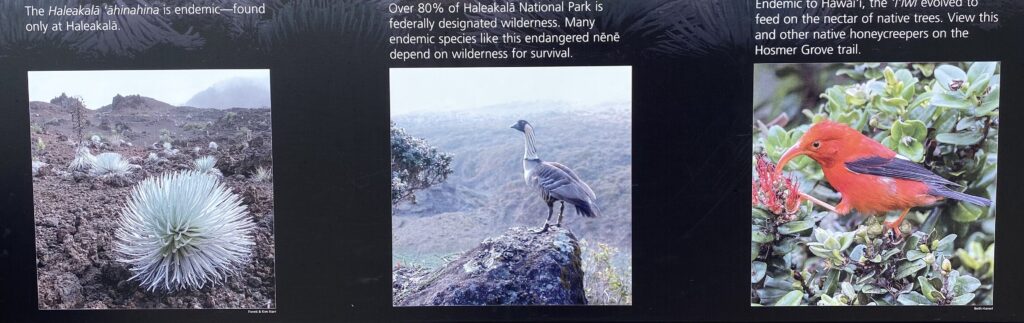

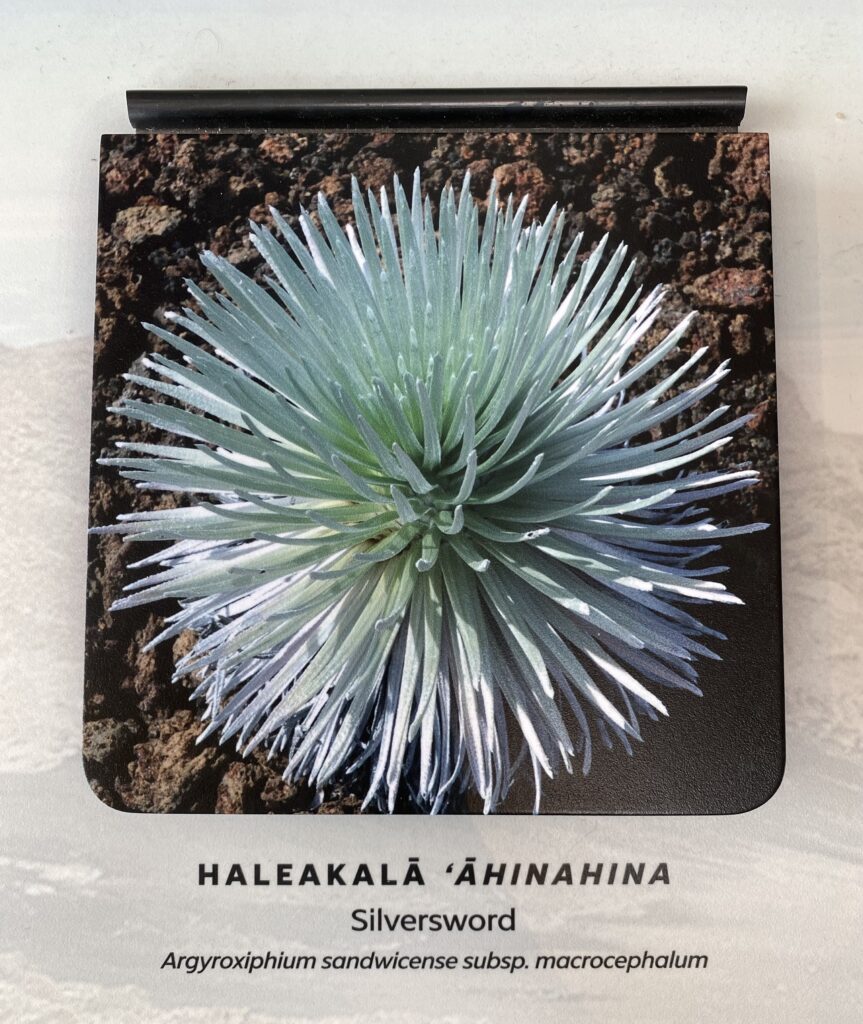

The Haleakala ‘ähinahina is endemic-found only at Haleakalä

Over 80% of Haleakala National Park is federally designated wilderness. Many endemic species like this endangered nêne depend on wilderness for survival.

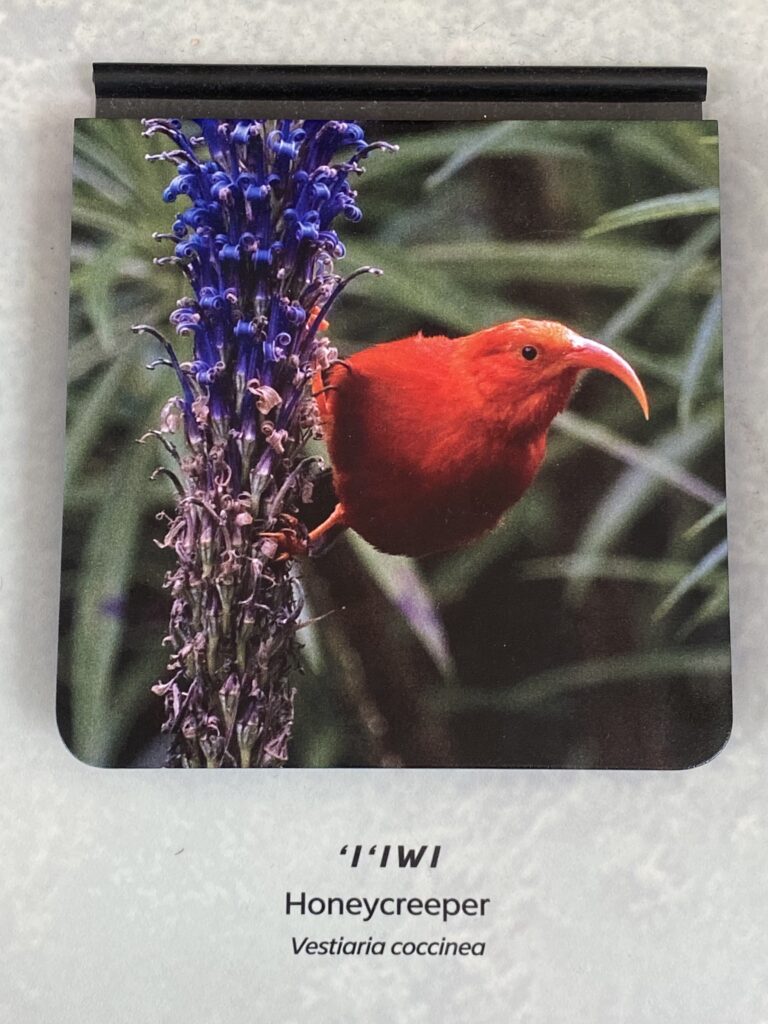

Endemic to Hawaii, the ‘i’iwi evolved to feed on the nectar of native trees. View this and other native honeycreepers on the Homer Grove trail.

An Isolated Island Home

Lava, rain, and wind continually shape the land you see. Trade winds shed their moisture over volcanoes, creating rain forests on one side and dry forests on the other. Native species depend on conditions unique to native ecosystems. As people change the islands, protected areas become even more critical for these species’ survival.

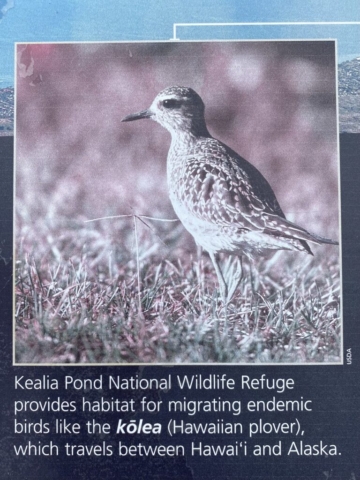

Kealia Pond National Wildlife Refuge provides habitat for migrating endemic birds like the kolea (Hawaiian plover), which travels between Hawaii and Alaska.

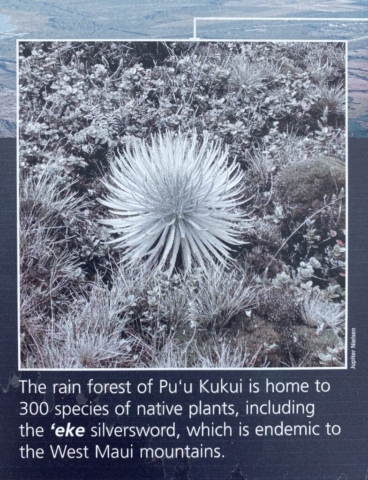

The rain forest of Pu’u Kukui is home to 300 species of native plants, including the ‘eke silversword, which is endemic to the West Maui mountains.

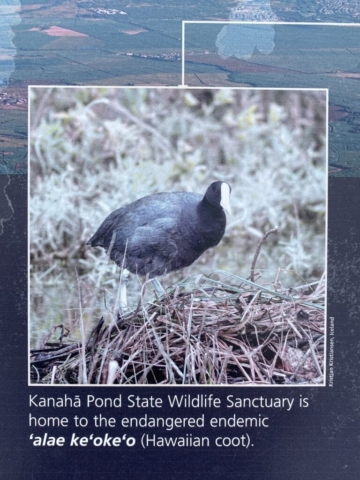

Kanaha Pond State Wildlife Sanctuary is home to the endangered endemic ‘alae ke*oke*o (Hawaiian coot).

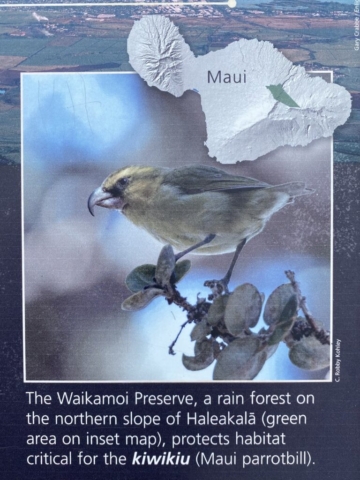

The Waikamoi Preserve, a rain forest on the northern slope of Haleakalā (green area on inset map), protects habitat critical for the kiwikiu (Maui parrotbill).

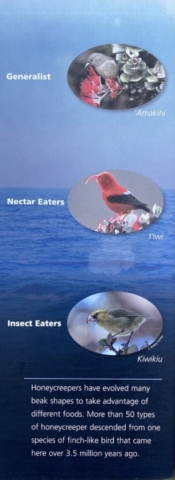

Honeycreepers have evolved many beak shapes to take advantage of different foods. More than 50 types of honeycreeper descended from one species of finch-like bird that came here over 3.5 million years ago.

A Long Journey

Wind, water, and wings brought life to Hawaii from faraway lands. Seeds, insects, and small plants and animals made the journey long before people set foot here. Adapting to local conditions and food, a few hundred colonizers evolved into thousands of native species. The estimated success rate is one successful colonizer every several thousand years.

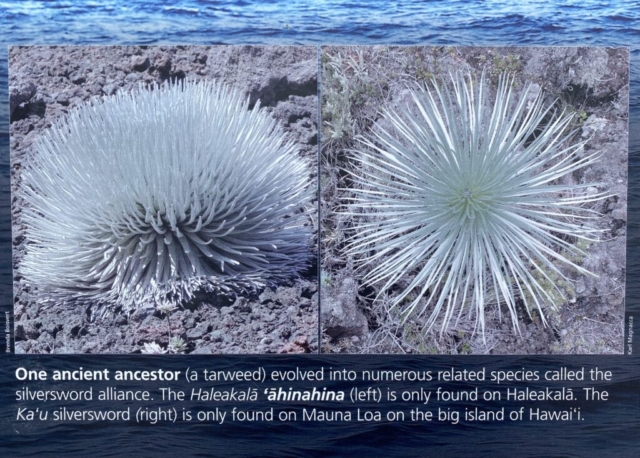

One ancient ancestor (a tarweed) evolved into numerous related species called the silversword alliance. The Haleakalä ‘ähinahina (left) is only found on Haleakala. The Ka’u silversword (right) is only found on Mauna Loa on the big island of Hawaii.

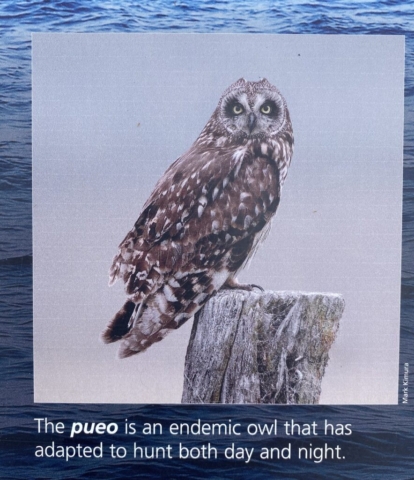

The pueo is an endemic owl that has adapted to hunt both day and night.

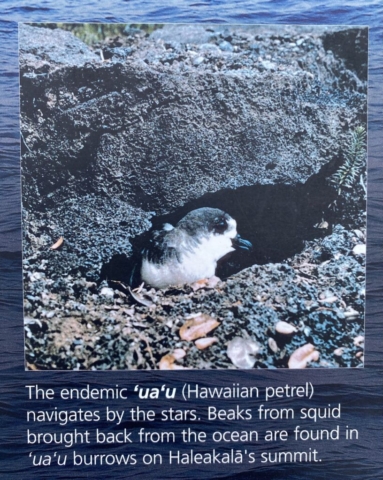

The endemic ua’u (Hawaiian petrel) navigates by the stars. Beaks from squid brought back from the ocean are found in va’u burrows on Haleakala’s summit.

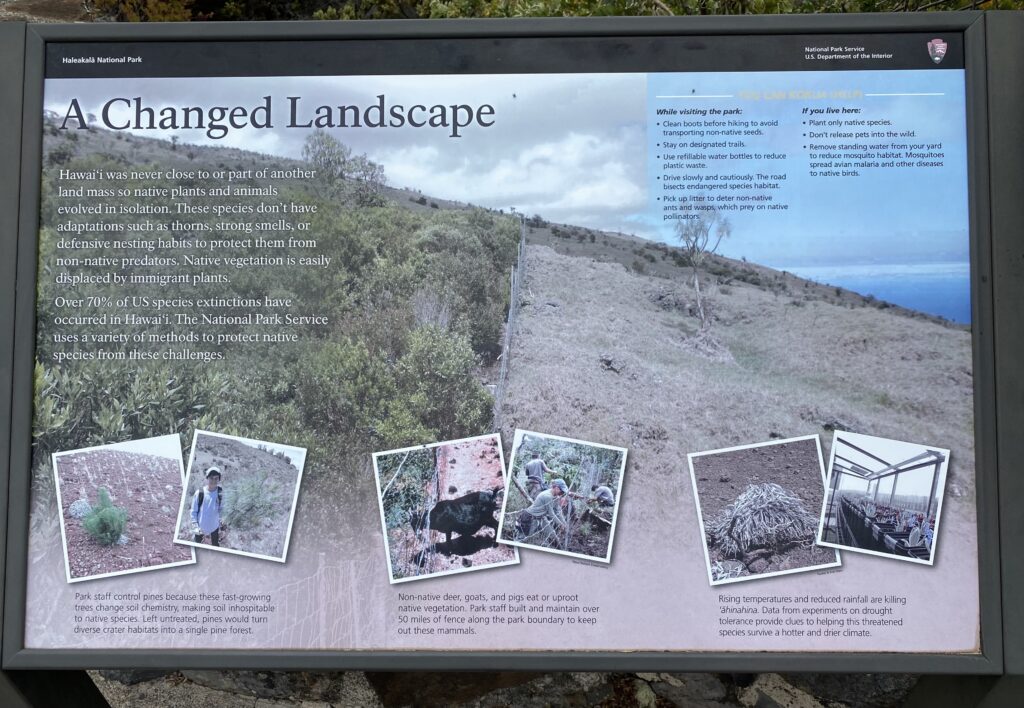

A Changed Landscape

Hawaii was never close to or part of another land mass so native plants and animals evolved in isolation. These species don’t have adaptations such as thorns, strong smells, or defensive nesting habits to protect them from non-native predators. Native vegetation is easily displaced by immigrant plants.

Over 70% of US species extinctions have occurred in Hawaii. The National Park Service uses a variety of methods to protect native species from these challenges.

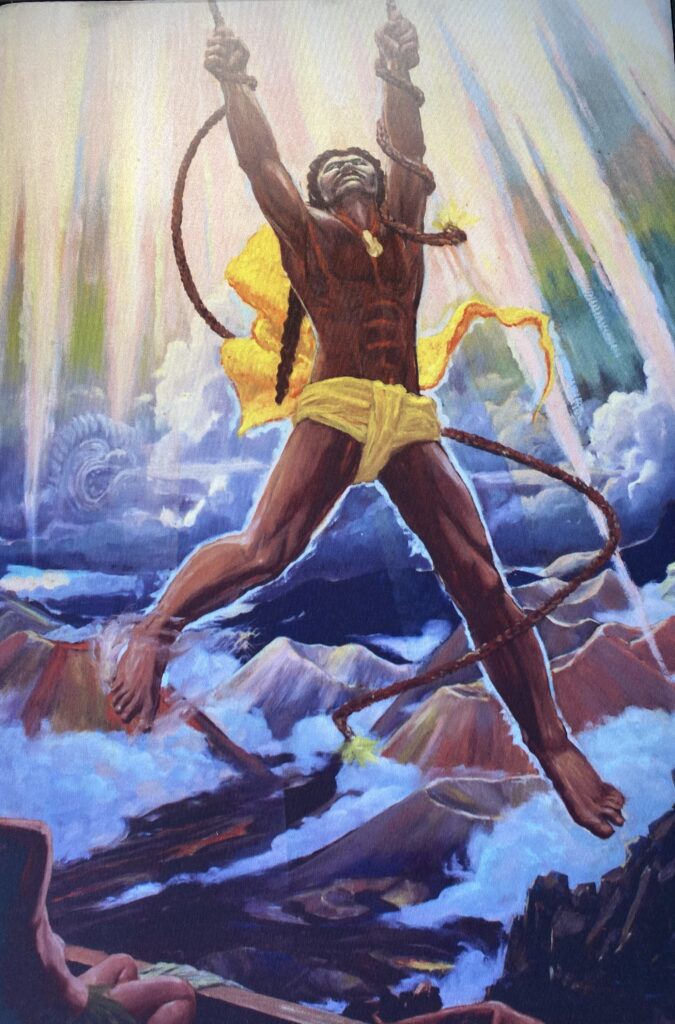

House of the sun

Hina asked her son, Demigod Maui, to travel to Haleakalã (House of the Sun) to slow down Lā (the sun) so her kapa (cloth) could dry properly. Maui climbed up Haleakala before dawn, lassoed the sun’s rays, and would not let go until Lā promised to slow down. This gave Hina time to dry her kapa and allowed other people time to finish their chores.

HALE A KA LA – HOUSE OF THE SUN

For countless generations, Haleakala has been part of Native Hawaiian history, legends, sites, and traditions that link the present to the past and future. The park protects the last or only homes for species found nowhere else on earth.

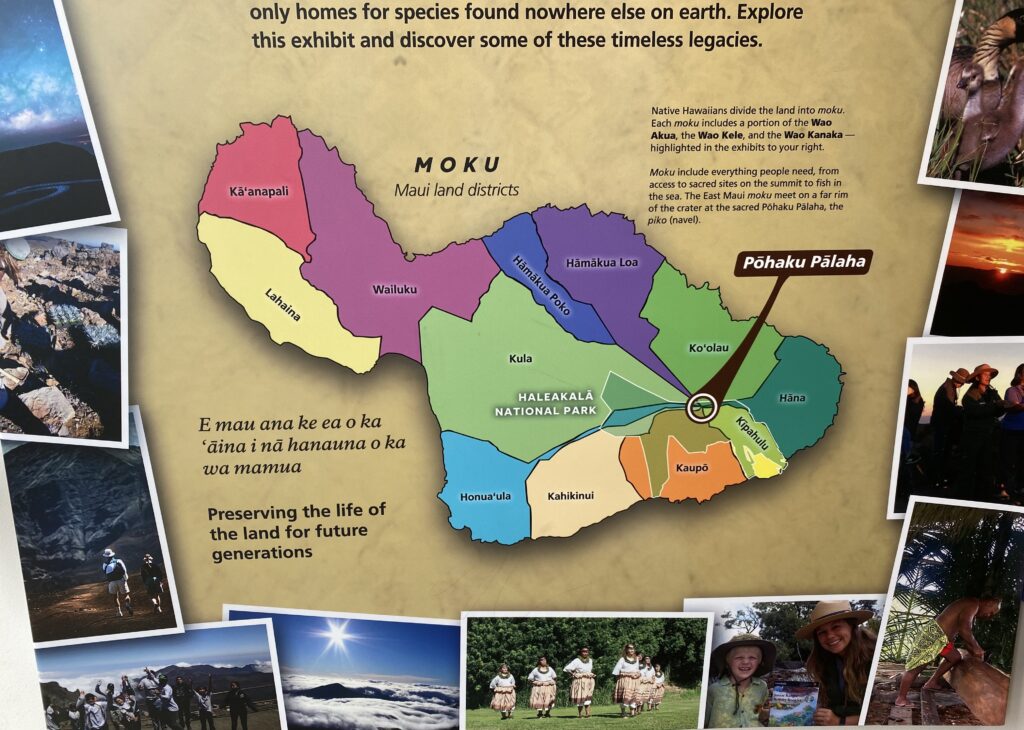

Moku

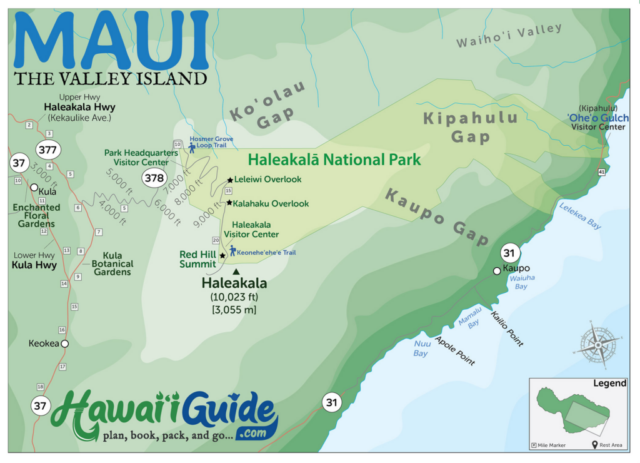

Native Hawaiians divide the land into moku.

Each moku includes a portion of the Wao Akua, the Wao Kele, and the Wao Kanaka – highlighted in the exhibits to your right.

Moku include everything people need, from access to sacred sites on the summit to fish in the sea. The East Maui moku meet on a far rim of the crater at the sacred Pöhaku Pälaha, the piko (navel).

WAO AKUA HOME OF THE GODS

The summit is sacred to Native Hawaiians, who come here to practice cultural traditions, rituals, and ceremonies passed down from their küpuna (elders).

In Ancient Hawaii, few people journeyed to the summit. They went there to learn how to use stars for navigation, perform ceremonies, hunt birds for feathers or meat, and quarry stone. The kako’i (adze maker) went to the summit of Haleakala to find the dense basalt stone needed for the head of the ko’i.

HALEAKALÄ ‘ÄHINAHINA

Silversword

Argyroxiphium sandwicense subsp. macrocephalum

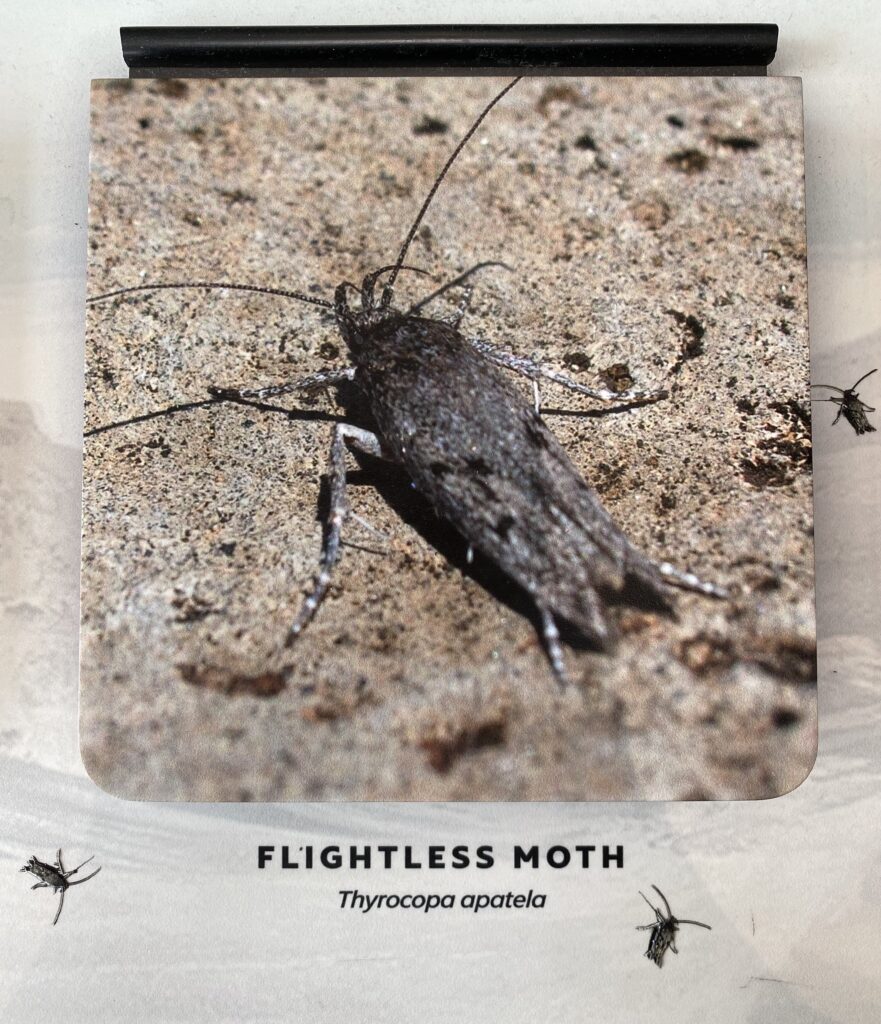

FLIGHTLESS MOTH

Thyrocopa apatela

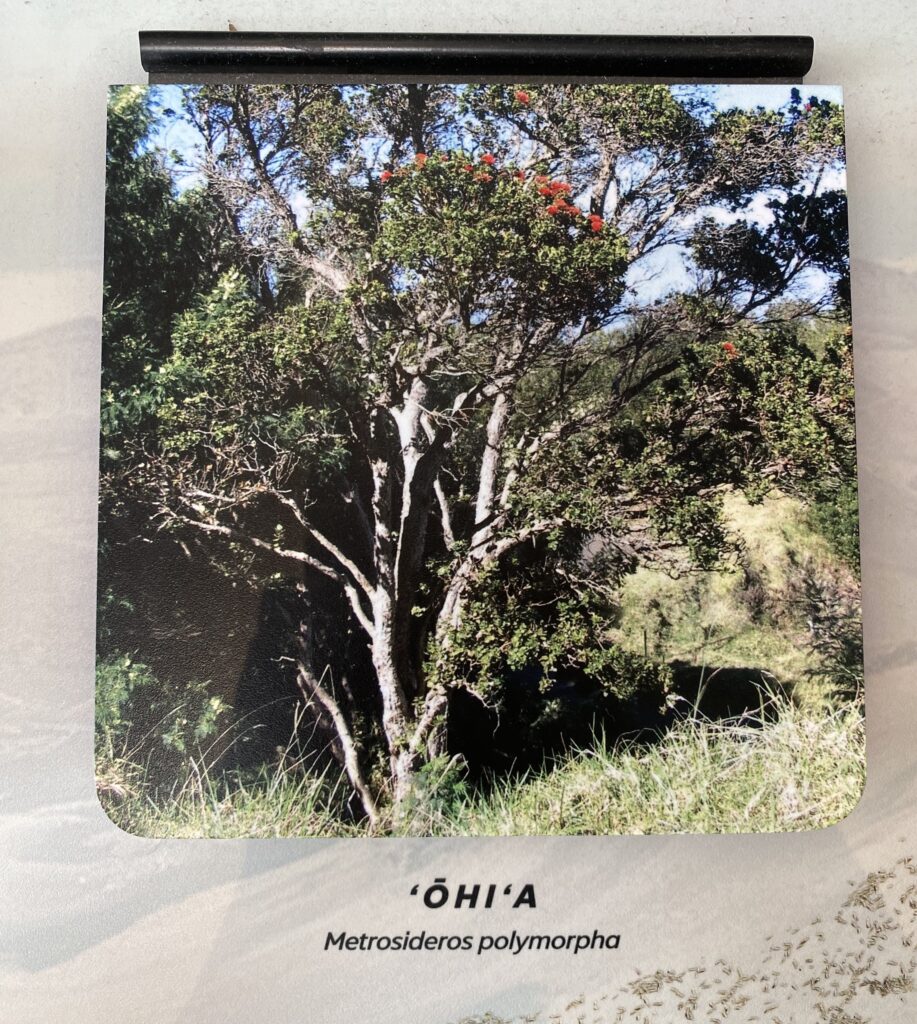

‘ŌHI’A

Metrosideros polymorpha

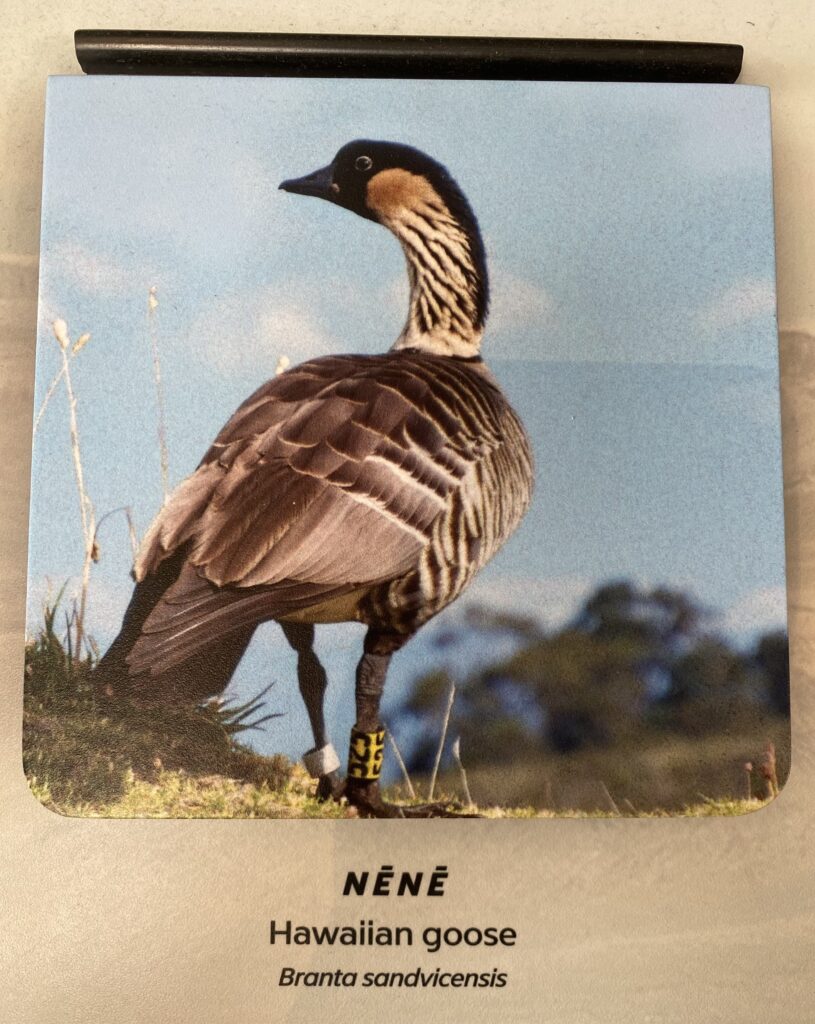

NĒNĒ

Hawaiian goose

Branta sandvicensis

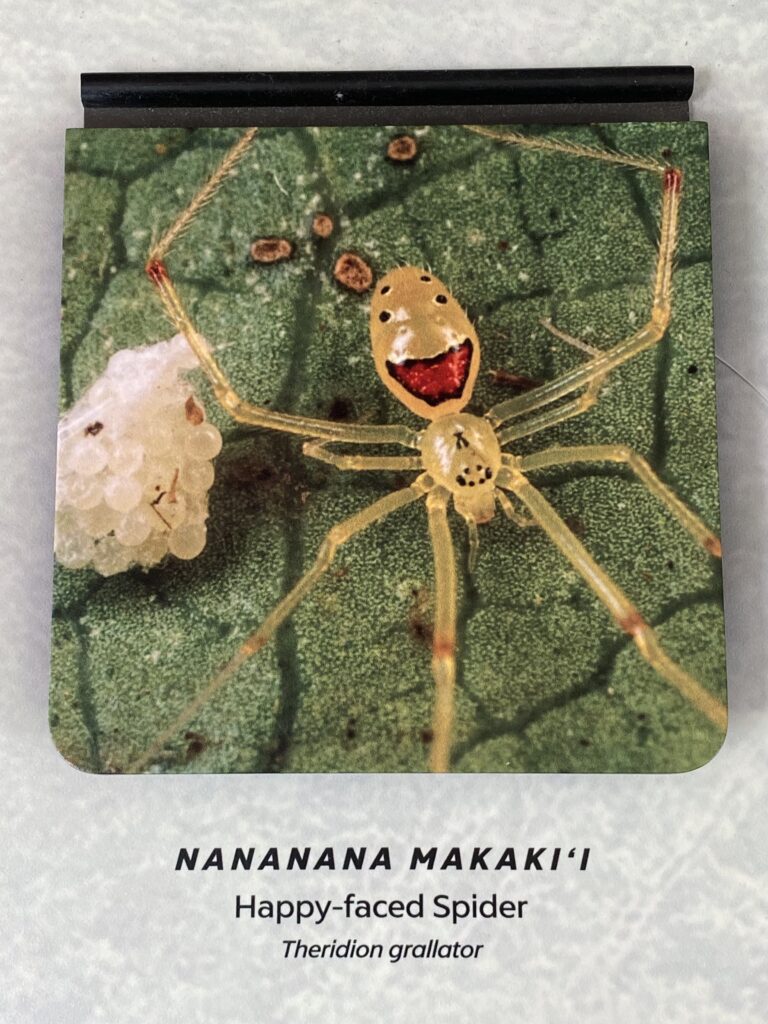

NANANANA MAKAKI”

Happy-faced Spider

Theridion grallator

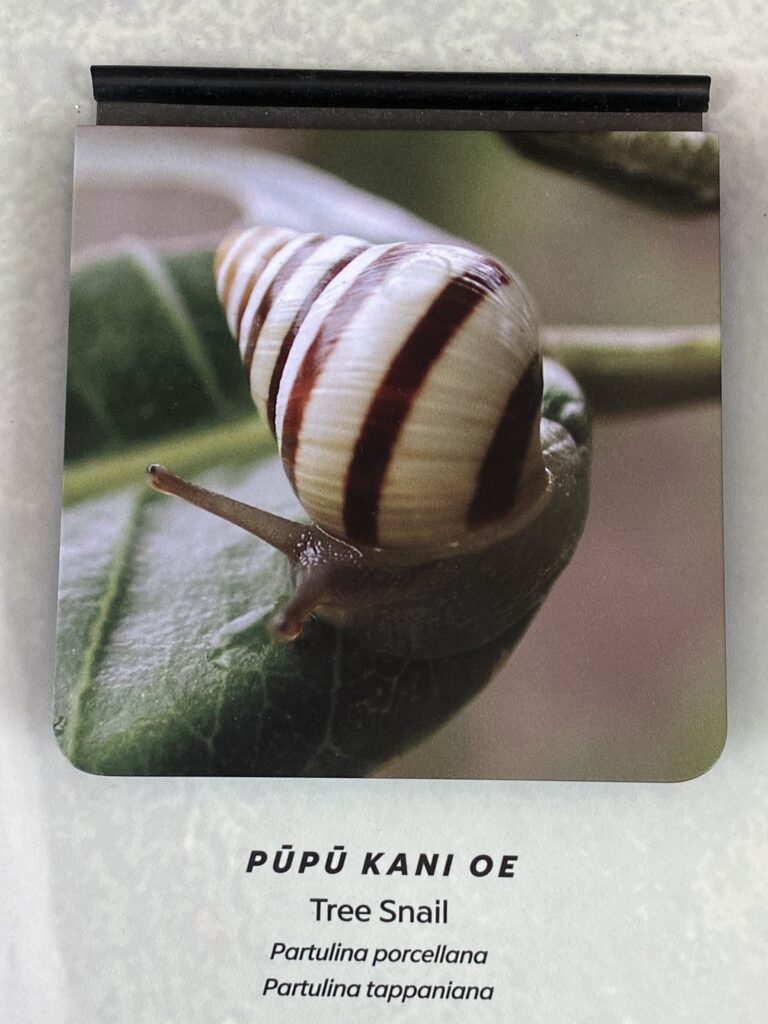

PŪPŪ KANI OE

Tree Snail

Partulina porcellana

Partulina tappaniana

‘I’I’WI

Honeycreeper

Vestiaria coccinea

‘ŌPE’APE’A

Hawaiian Hoary Bat

Lasiurus cinereus semotus

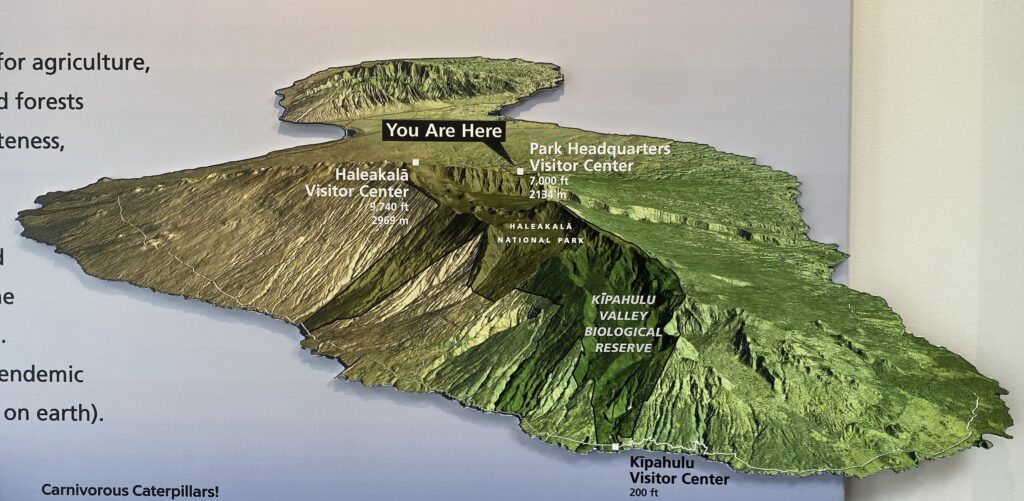

WAO KELE – A PLACE OF LIFE-GIVING WATERS

A place of transition between people and the gods, the forested Wao Kele is the source of wai ola (life-giving waters).

In the 1800s, forests were cleared for agriculture, ranching, and homes. Some upland forests remained untouched due to remoteness, elevation, or cultural significance.

In 1969, several upland forests and bogs were added to the park as the Kipahulu Valley Biological Reserve.

Many of the Reserve’s species are endemic to East Maui (found nowhere else on earth).

WAO KANAKA – A PLACE FOR LIFE AND CULTIVATION

I ka nānā no a ‘ike (By observing, one learns)

Wao Kanaka is where people live and work, sharing their skills and talents with the community.

One of the best places to experience this knowledge is in the Kipahulu District, near Hana. Visitors can view archeological sites and learn Native Hawaiian practices from park staff and community members.

Keep traditions alive

Watch craftspeople turn native resources into traditional food, goods, and tools.

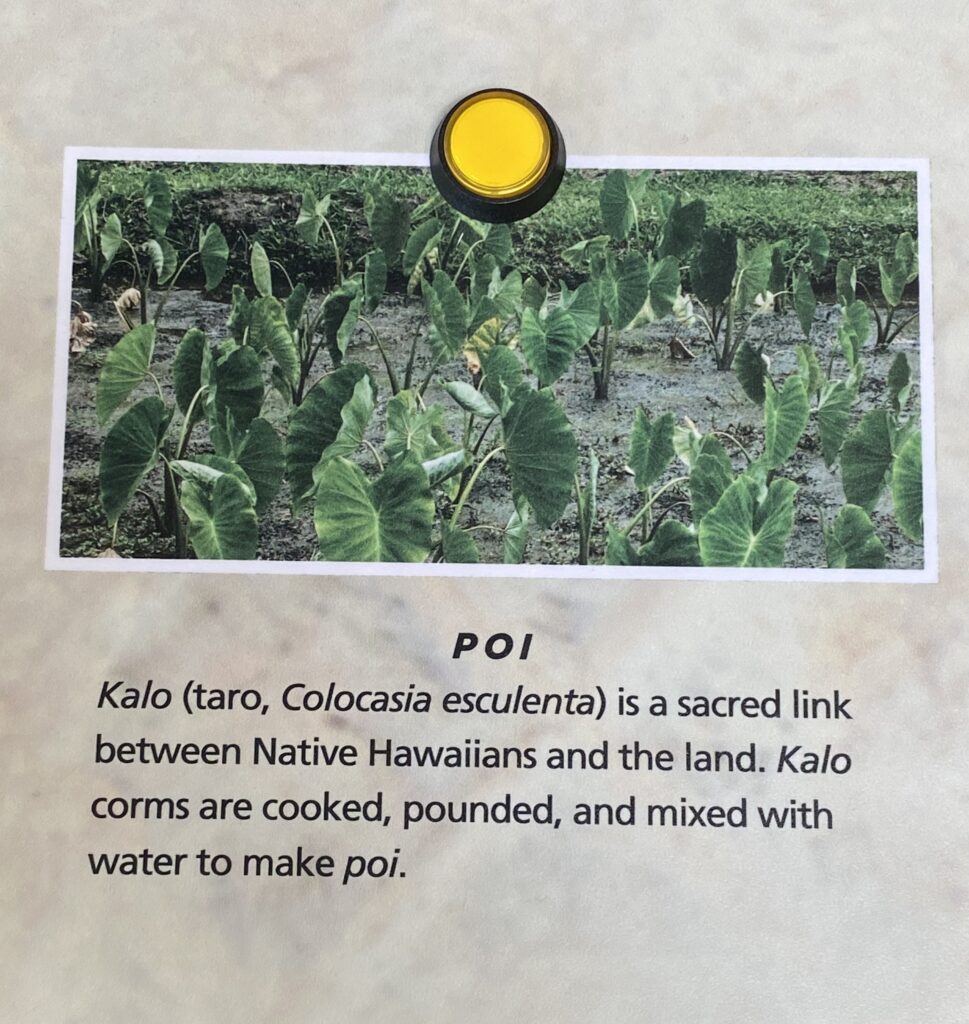

POI

Kalo (taro, Colocasia esculenta) is a sacred link between Native Hawaiians and the land. Kalo corms are cooked, pounded, and mixed with water to make poi.

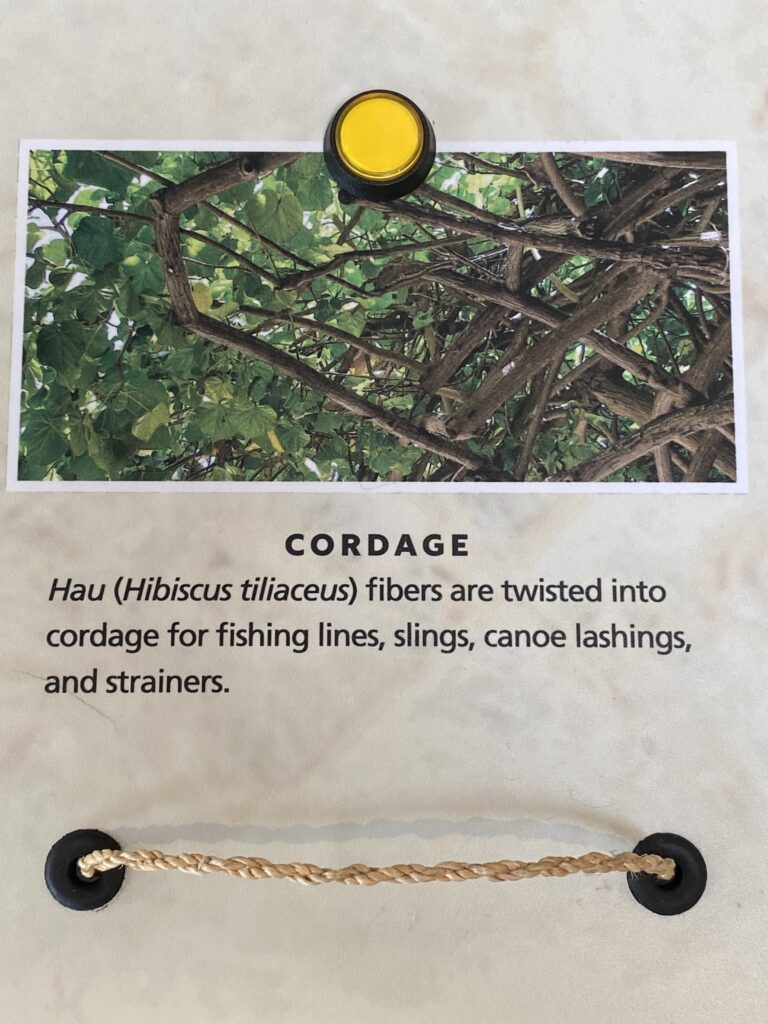

CORDAGE

Hau (Hibiscus tiliaceus) fibers are twisted into cordage for fishing lines, slings, canoe lashings, and strainers.

WOVEN GOODS

Green or dried hala (Pandanus tectorius) leaves are woven into sails, mats, roofs, and baskets.

WA’A

Koa (Acacia koa) wood is cut, sanded, and finished to make hoe nenue (paddles).

Instant Weather

In just a few minutes the conditions here near the summit of Haleakala can shift from summer to winter. You can feel the difference, and from this overlook you can watch the weather forming at your feet. In this wind-driven world, clouds flow daily into the summit basin, causing sudden drops in temperature.

Hawaii – The Big Island

The island of Hawaii, the largest of the Hawaiian Islands, is often visible in the distance.

Its two dominant volcanic peaks 13,796-ft.

(4205 m) Mauna Kea on the left and 13,667-ft. (4169 m) Mauna Loa on therright-usually tower above the clouds. These peaks are about 80 and 100 miles (128 and 160 km) southeast of Haleakalä.

The Big Island,” as it is often called, is still growing. Long-lived eruptions on the east rift zone of Kilauea Volcano have added hundreds of acres of land to the shores of Hawaii in recent decades. With more than 4,000 square miles (10,400 sq km), Hawaii is almost twice the size of all the other Hawaiian Islands combined.

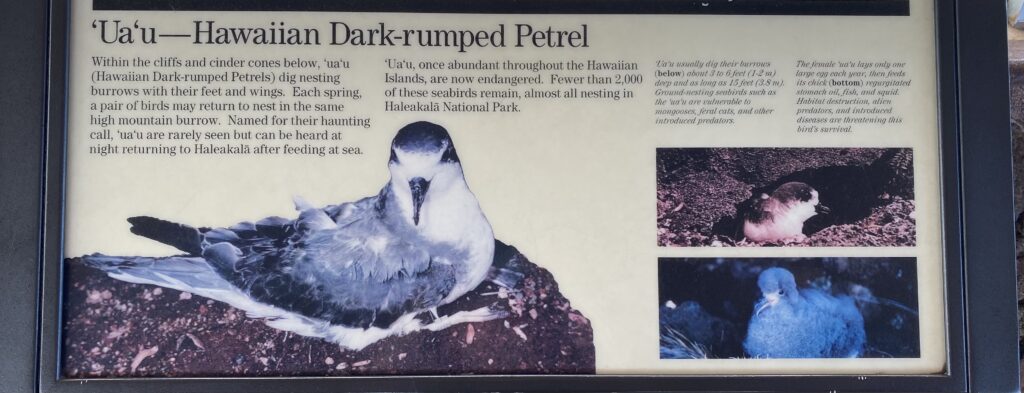

‘Ua’u-Hawaiian Dark-rumped Petrel

Within the cliffs and cinder cones below, ‘va’u (Hawaiian Dark-rumped Petrels) dig nesting burrows with their feet and wings. Each spring, a pair of birds may return to nest in the same high mountain burrow. Named for their haunting call, ‘ua’u are rarely seen but can be heard at night returning to Haleakalā after feeding at sea.

‘Ua’u, once abundant throughout the Hawaiian Islands, are now endangered. Fewer than 2,000 of these seabirds remain, almost all nesting in Haleakala National Park.

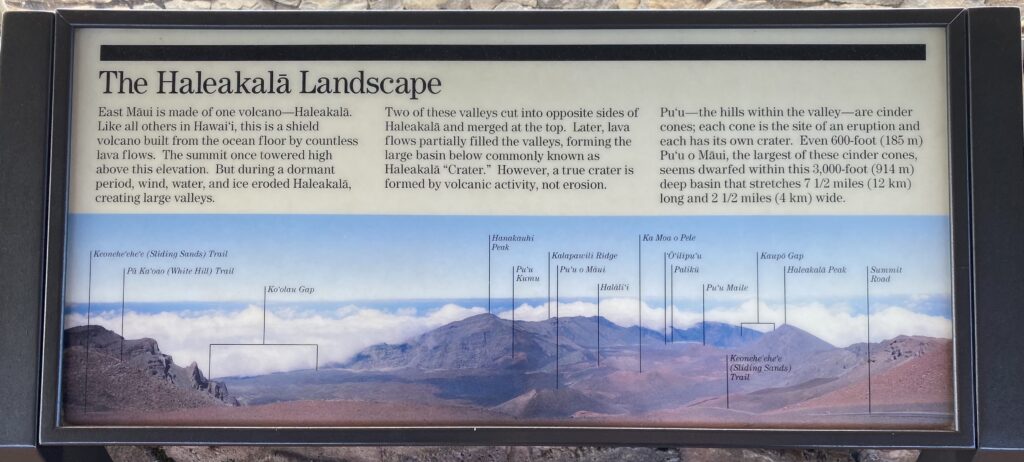

The Haleakala Landscape

East Maui is made of one volcano-Haleakala.

Like all others in Hawaii, this is a shield volcano built from the ocean floor by countless lava flows. The summit once towered high above this elevation. But during a dormant period, wind, water, and ice eroded Haleakalä, creating large valleys.

Two of these valleys cut into opposite sides of Haleakala and merged at the top. Later, lava flows partially filled the valleys, forming the large basin below commonly known as Haleakala “Crater.” However, a true crater is formed by volcanic activity, not erosion.

Pu’u-the hills within the valley-are cinder cones; each cone is the site of an eruption and each has its own crater. Even 600-foot (185 m)

Pu’ o Maui, the largest of these cinder cones, seems dwarfed within this 3,000-foot (914 m) deep basin that stretches 7 1/2 miles (12 km) long and 2 1/2 miles (4 km) wide.

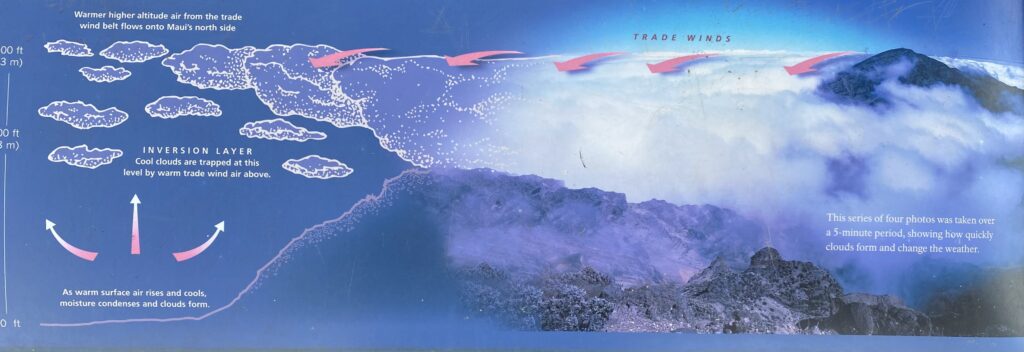

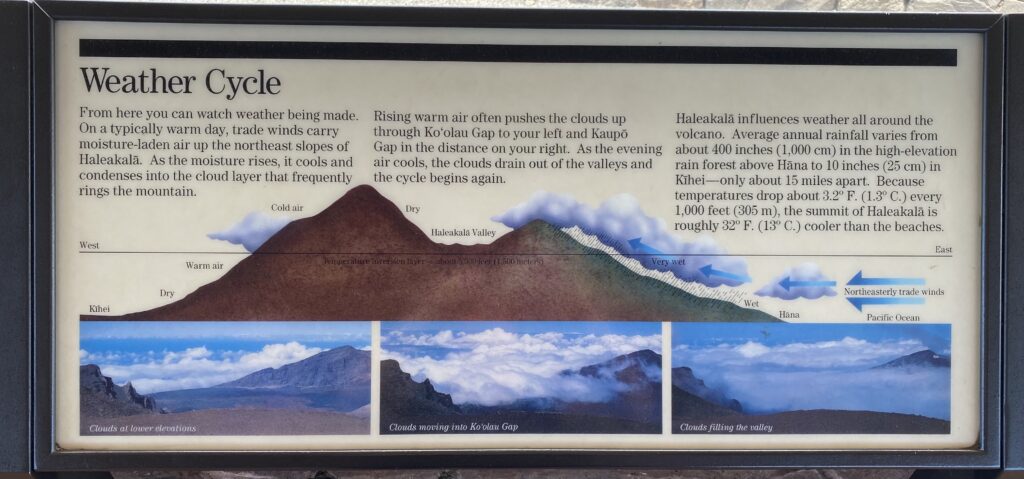

Weather Cycle

From here you can watch weather being made.

On a typically warm day, trade winds carry moisture-laden air up the northeast slopes of Haleakala. As the moisture rises, it cools and condenses into the cloud layer that frequently rings the mountain.

Rising warm air often pushes the clouds up through Ko’olau Gap to your left and Kaupo Gap in the distance on your right. As the evening air cools, the clouds drain out of the valleys and the cycle begins again.

Haleakala influences weather all around the volcano. Average annual rainfall varies from about 400 inches (1,000 cm) in the high-elevatic rain forest above Hana to 10 inches (25 cm) in Kihei -only about 15 miles apart. Because temperatures drop about 3.2° F. (1.3° C.) every 1,000 feet (305 m), the summit of Haleakala is roughly 32° F. (13° C.) cooler than the beaches.

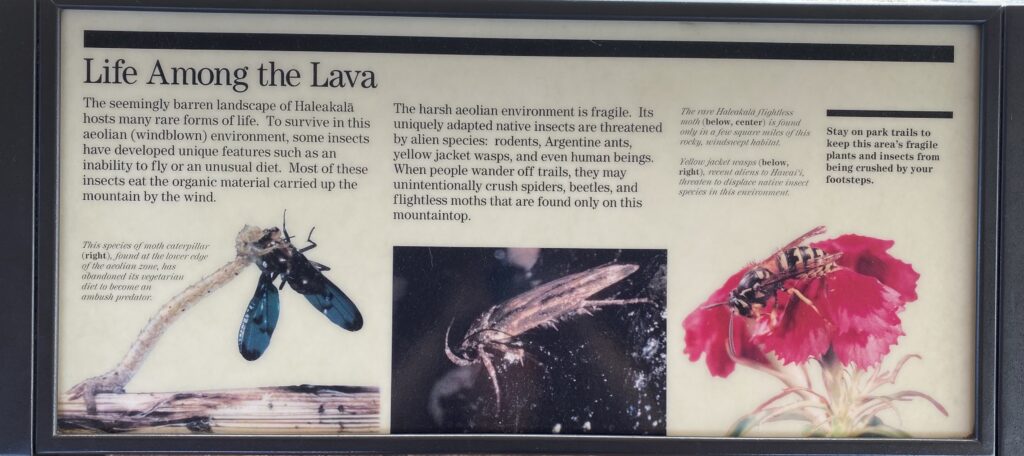

Life Among the Lava

The seemingly barren landscape of Haleakala hosts many rare forms of life. To survive in this aeolian (windblown) environment, some insects have developed unique features such as an inability to fly or an unusual diet. Most of these insects eat the organic material carried up the mountain by the wind.

The harsh aeolian environment is fragile. Its uniquely adapted native insects are threatened by alien species: rodents, Argentine ants, yellow jacket wasps, and even human beings.

When people wander off trails, they may unintentionally crush spiders, beetles, and flightless moths that are found only on this mountaintop.

Silversword

While there, look for the rare Hawaii silversword that grows here. Silverswords take up to 50 years to bloom and then die.

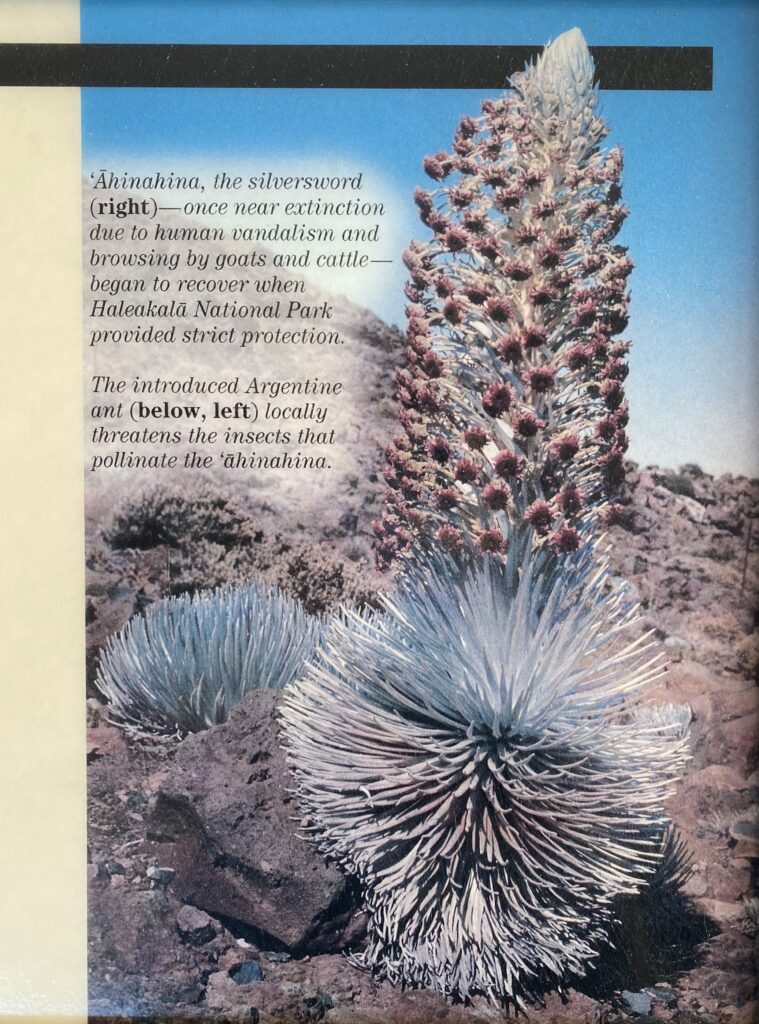

Ähinahina, the silversword (right)-once near extinction due to human vandalism and browsing by goats and cattle-began to recover when Haleakala National Park provided strict protection.

The introduced Argentine ant (below, left locally threatens the insects that pollinate the ‘ahinahina.

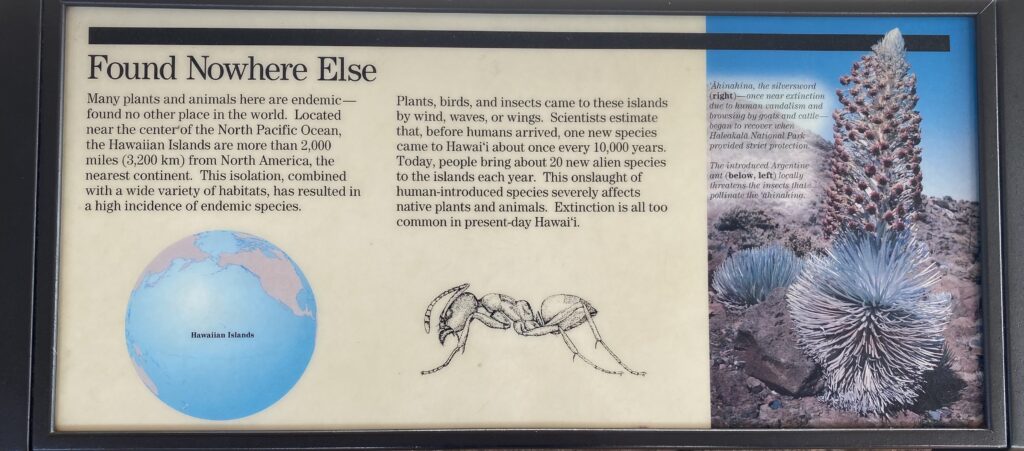

Found Nowhere Else

Many plants and animals here are endemic-found no other place in the world. Located near the center of the North Pacific Ocean, the Hawaiian Islands are more than 2,000 miles (3,200 km) from North America, the nearest continent. This isolation, combined with a wide variety of habitats, has resulted in a high incidence of endemic species.

Plants, birds, and insects came to these islands by wind, waves, or wings. Scientists estimate that, before humans arrived, one new species came to Hawaii about once every 10,000 years.

Today, people bring about 20 new alien species to the islands each year. This onslaught of human introduced species severely affects native plants and animals. Extinction is all too common in present-day Hawaii.

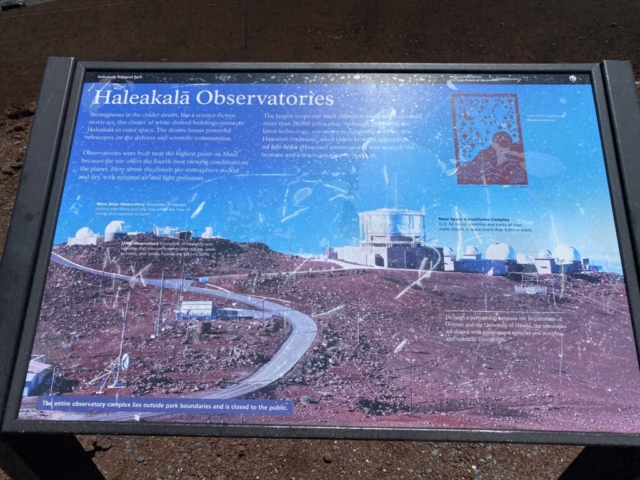

Haleakala Observatory

Incongruous in the cinder desert, like a science-fiction movie set, this cluster of white-domed buildings connects Haleakala to outer space. The domes house powerful telescopes for the defense and scientific communities.

Observatories were built near the highest point on Maul because the site offers the fourth-best viewing conditions on the planet. Here above the,clouds the atmosphere is-clear and dry, with minimal air and light pollution.

The largest scope can track objects as small as a basketball more than 20,000 miles away. Although employing the latest technology, astronomy is consistent with ancient Hawaiian traditions, when elders brought apprentice na kilo hoku (Hawaiian astronomers) here to study the heavens and learn to navigate by the stars.

Pa Ka’oao White Hill Trail

The trail climbs to the top of a volcanic cinder cone for views of the Haleakalā

Wilderness Area and the highest peaks of the Big Island. At first glance the trail environment seems nothing but barren rock. Yet these rocks are living habitat for nesting ua u, ‘ähinahina (silversword), and a dramatic mini-world of wolf spiders, flightless moths, and yellow-faced bees. Although the summit can appear hostile to people, temporary shelters, visible on the rocky slopes below the trail, testify to a long human history.

Life of a Volcano

Haleakala

Haleakala is dying. No molten lavas have issued from the mountain since about 1790. Although it may erupt again, the great volcano is nearing the end of a fiery history which began ahout 800,000 years ago. Erosion, now the deminant force, is gradually wearing the aging volcano down.

Surprisingly, the “crater” you see today is not of volcanic origin. Rainwater coursing down the slopes and out the gaps has carried away millions of tons of volcanic rocks through the ages, leaving behind an expansive, steep-walled erosional depression. During a period of renewed volcanic activity, lava flows and small cinder cones erupted from the floor.

These, too, are beginning to wear away as perennial rains take their toll.

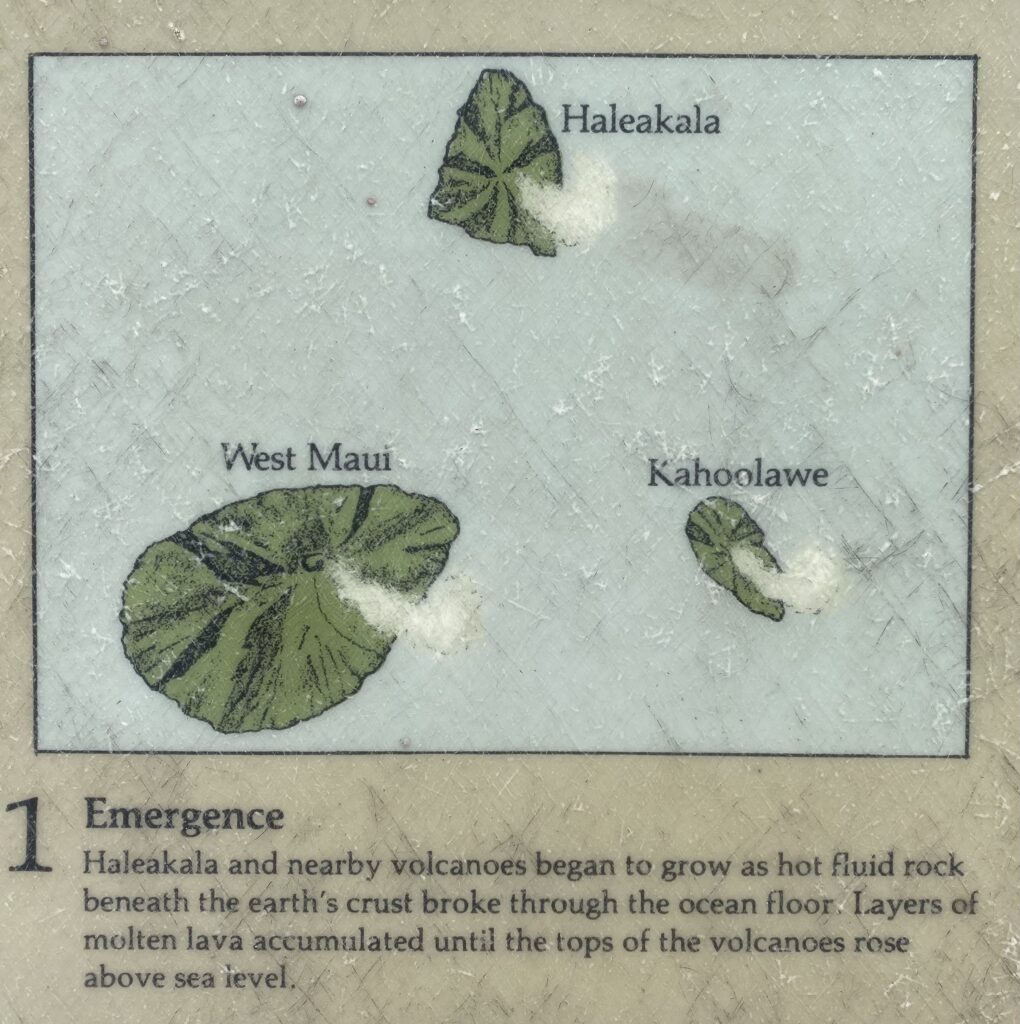

- Emergence

Haleakala and nearby volcanoes began to grow as hot fluid rock beneath the earth’s crust broke through the ocean floor. [ayers of molten lava accumulated until the tops of the volcanoes rose above sea level

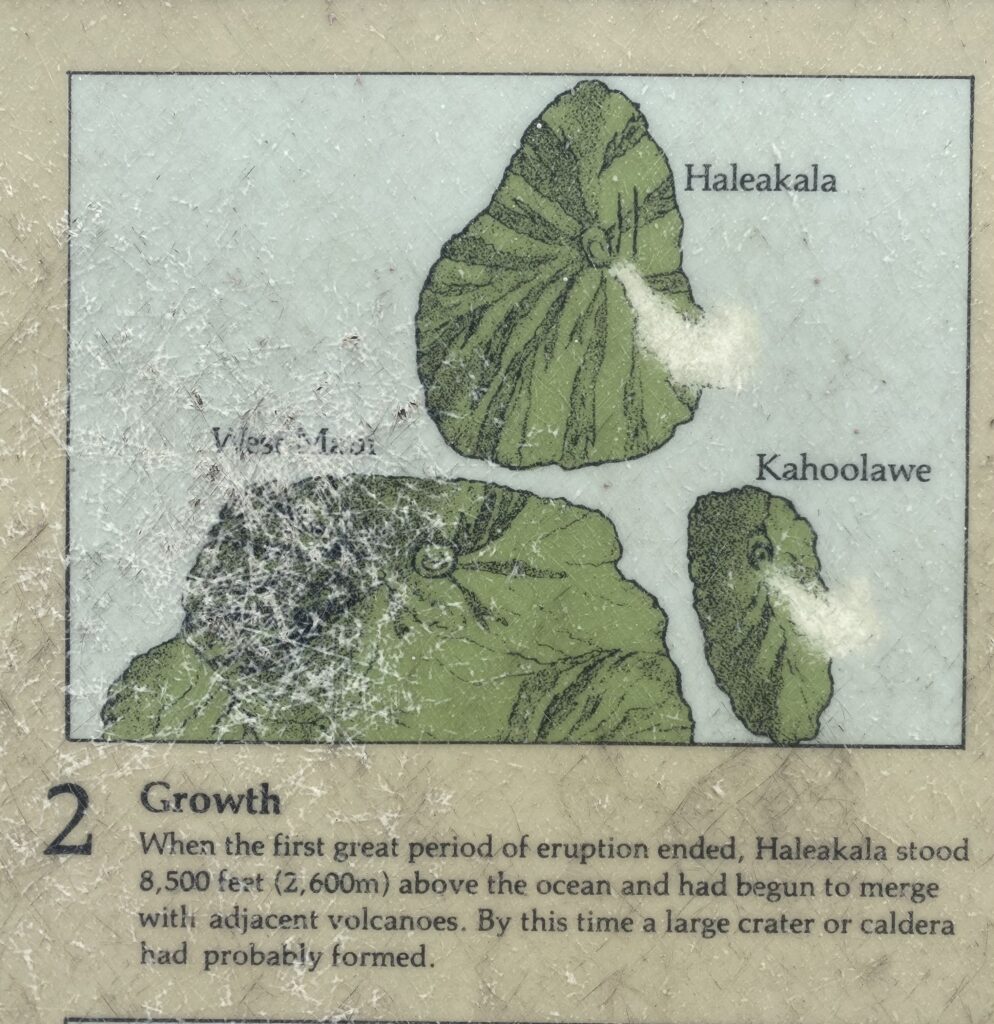

- Growth

When the first great period of eruption ended, Haleakala stood 8,500 fest (2,600m) above the ocean and had begun to merge with adjacent volcanoes. By this time a large crater or caldera had probably formed.

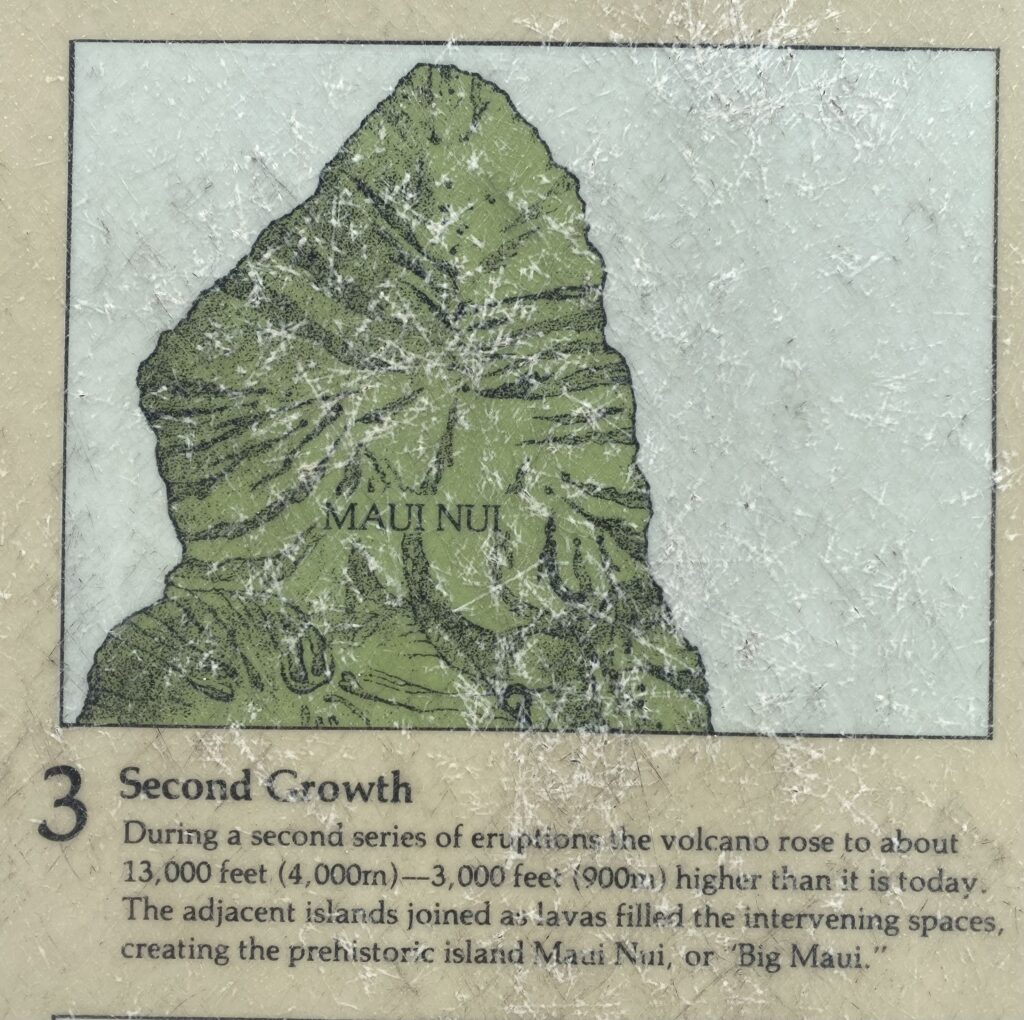

3. Second Growth

During a second series of eruptions the volcano rose to about 13,000 feet. (4,000) –3,000 fee: (900m) higher than it is today.

The adjacent islands joined a lavas filled the intervening spaces, creating the prehistoric island Madi Nui, Big Maui

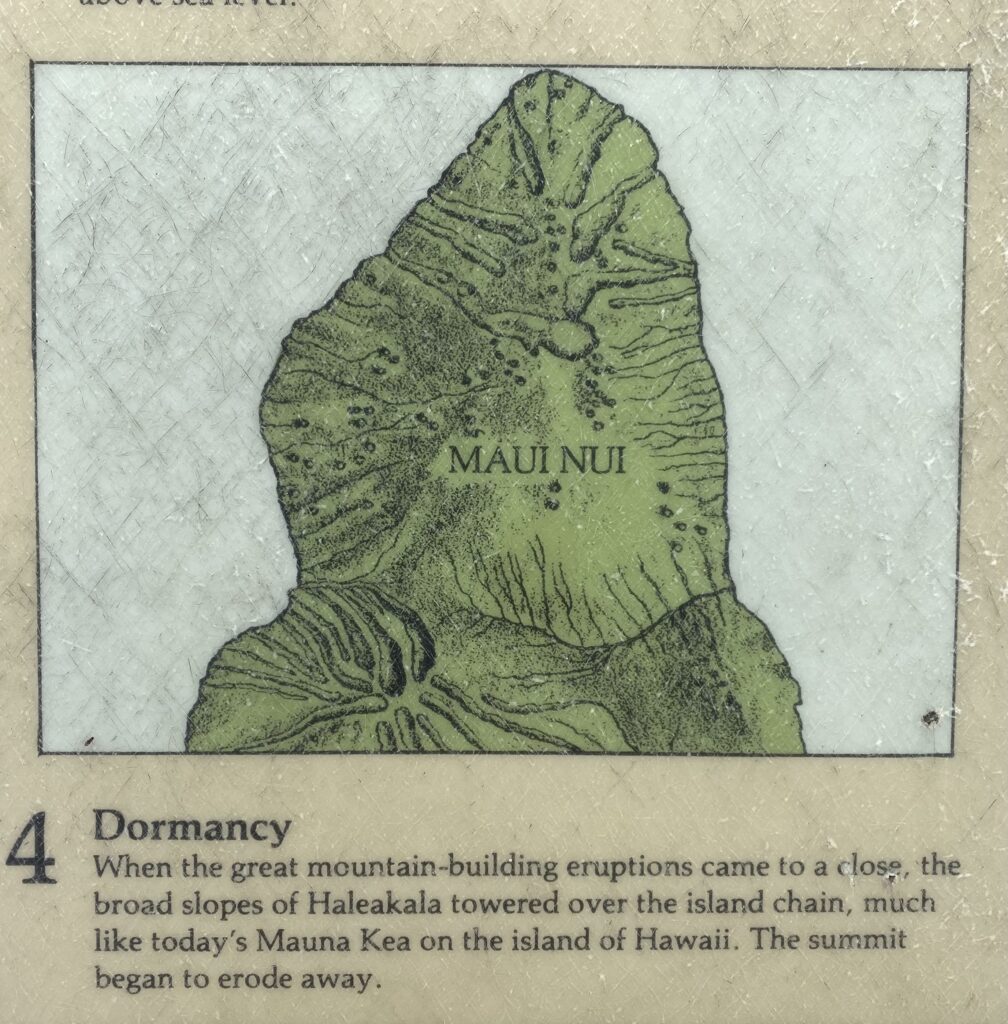

4. Dormancy

When the great mountain-building eruptions came to a close, the broad slopes of Haleakala towered over the island chain, much like today’s Mauna Kea on the island of Hawaii. The summit began to erode away.

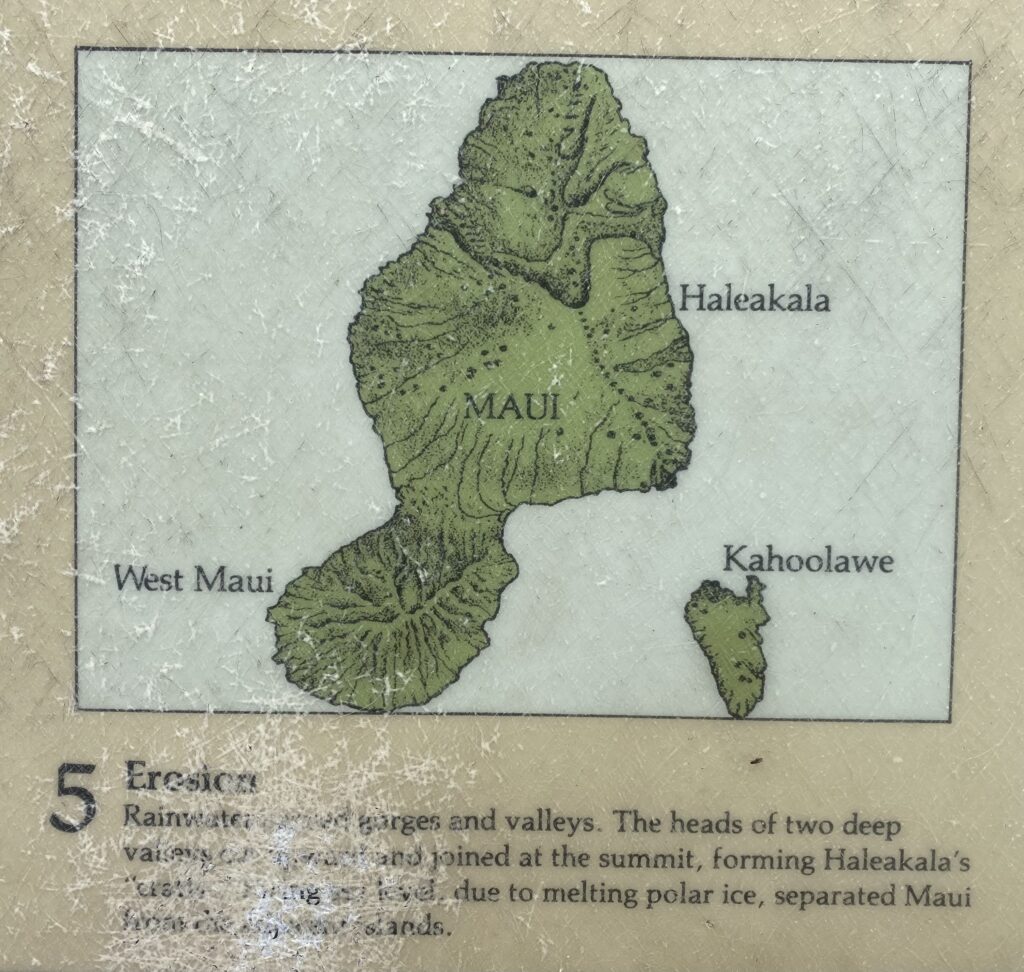

5. Erosion

Rainwater created gorges and valleys.

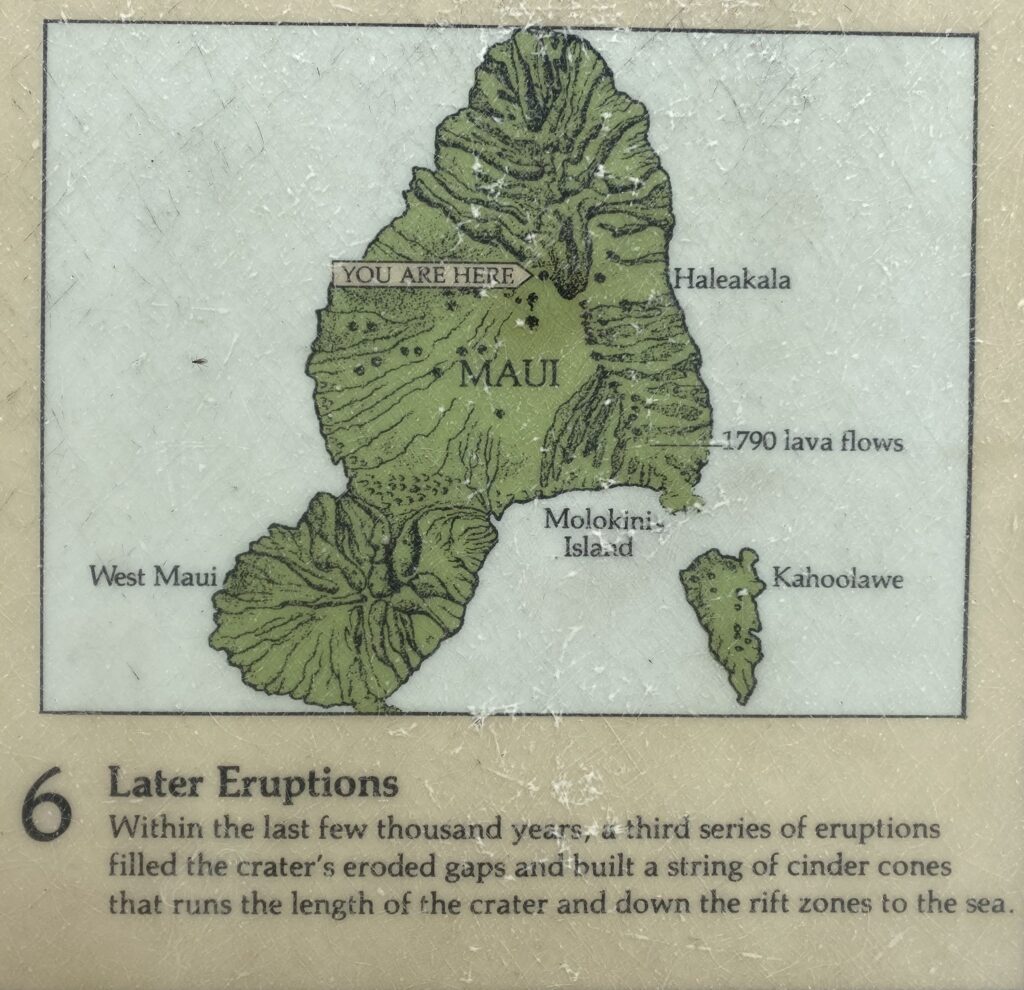

6. Later Eruptions

Within the last few thousand years, third series of eruptions filled the crater’s eroded gaps and built a string of cinder cones that runs the length of the crater and down the rift zones to the sea.

Āhinahina

Argyroxiphium sandwicense subsp. macrocephalum)

Endemic

An ‘āhinahina can bloom in its first years of life or may wait several decades to send up the densely fragrant stalk of hundreds of purple sunflower-like blooms. The plant sheds tiny, light seeds and then dies. Furry, reflective (solar radiation is brutal up here), silver spiky leaves catch drifting cloud moisture and aim it toward the plant base. Fragile roots extend around the base; keeping your distance from living ‘āhinahina is the best way to protect them. Goats brought to Hawai‘i after western contact nearly destroyed the ‘āhinahina population. Haleakalā was one of the first national parks to be fenced (in the 1980s) to keep out non-native goats, deer, and pigs.The fence is maintained and continually checked by park staff.

- https://www.nps.gov/hale/learn/nature/plants-of-the-summit-district.htm

Pūkiawe

(Leptecophylla tameiameiae)

Endemic

Tiny pink and white berries festoon this hardy shrub year-round and are food for nēnē, the endangered Hawaiian goose and state bird. Pūkiawe was once found all the way to the shoreline, but now mostly grows in high-elevation protected areas. Cultural uses of pūkiawe included purification in the burning plant’s smoke by ali‘i (royalty or chiefs) to lift the kapu (taboo) that forbade mingling with commoners. The berries and stiff greenery are also artfully woven into lei.

- https://www.nps.gov/hale/learn/nature/plants-of-the-summit-district.htm

Heart of Maui

https://www.nps.gov/media/video/view.htm?id=1184F741-74F4-46CC-BA60-B6933A6A2641

This short National Park Service documentary film follows two biologists working to save rare and endemic forest birds in Haleakalā National Park.

DURATION

7 minutes, 29 seconds

CREDIT

NPS / David Ehrenberg

“It’s hard for people to feel passionate about saving something that they don’t have a personal experience with.” – Chris Warren, Forest Bird Coordinator at Haleakala National Park

Haleakalā National Park Brochure

This guide is created by kanaka maoli (native Hawaiians) of the island of Maui to ensure that through generational knowledge, kanaka maoli natural and cultural resources are cared for with appropriate respect and behavior by all who enter Haleakala National Park,

‘Aha Moku

A Sense of Place

Unlike western land and ocean use practices, the ‘Aha Moku system is based on observational knowledge that provides a management system of proper stewardship of both land and ocean resources. Land use was determined by the availability of wai ola (life-giving water). Hawaiian terms for land divisions such as mokupuni, moku, and ahupua’a are given to these land and ocean areas. This map of Maui names and delineates the Moku land divisions.

Each of these districts is known by its natural features, place names and environmental conditions. Specific areas have diverse natural resources and are therefore managed in different ways.

The ‘Aha Moku system is the foundation which provides känaka maoli (Native Hawaiian) a lifetime reverence for self-sustainability.

For kanaka maoli, this system continues today and into the future.

Wao Akua, Wao Kele, Wao Kanaka, ‘Ae Kai, Kai Malolo, and Kai Uli are examples of designated management zones to assure that proper practices, uses and care are established within each mokul ahupua’a. The National Park Service has accepted this kuleana (responsibility). Kuleana of all these resources starts from the heavens and descends down upon the land and continues into the oceans of Kipahulu, Ka’apahu and Nu’u Mauka. The National Park Service – Haleakala National Park partners with kanaka maoli for guidance and support in efforts to educate residents and visitors alike regarding a sense of place.

Wao Akua

Sacred for the Gods

Long before modern science delineated areas for resources management, känaka maoli had a land division system already in place. This area is known as the Wao Akua. With this designa-tion, känaka maoli believe that these areas are inhabited only by nã akua (deities) and are accountable to its sacred nature, which is still honored today. These places are kapu (sacred) and closed to public access.

Wao Kele

Spiritual Transition

Känaka maoli determined the Wao Kele as the boundary between man and the deities. It is, among many other things, an area for observational learning, seed bank protection, medicinal practices, and life dependent resources. The kia’ (guardian) has kuleana to malama (care for) the Wao Kele, because this is the source for wai ola (ife giving waters). This kuleana is understood by all who are dependent on these resources. Like the Wao Akua, the Wao Kele has the same kapu and is closed to public access.

Wao Kanaka

Life and Cultivation

Känaka maoli inhabit the area of Wao Kanaka. Here, eac one contributes to the life of the community through the specific kuleana. Examples of kuleana discplines are:

Kahuna (spiritual advisor)

Kahuna lapa’au (wellness advisor)

Mahiai (agricultural advisor)

Lawai*a (fisheries advisor)

The kupaäina (lineal descendants) have kuleana derive from this sense of place. Some kapu are based upon Hawaiiar calendar seasons. Upon entering these areas, it is important to know that a malihini (visitor), much like the kupa’äina, has kuleana to that place.

Alaheleakala: Na Wao

“…Hānau ka pō…”

The Kumulipo is an ancient, sacred,

oral tradition. It has multiple life applications for all kânaka maoli

(Native Hawaiians), and indeed, for all people. This Kumulipo chant describes the relationships between people and resources, both spiritual and physical.

Spiritual relationships with all resources come first. From Nā Akua (the deities) come the resources, and the people are its stewards. In the Kumulipo, all resources are explained and inventoried so that proper care is applied through kuleana (responsibility).

KULEANA

Hawaiians believe in the concept of kuleana (responsibility). Kuleana is passed on to us from our küpuna (ancestors). Our duty is to perpetuate this kuleana and our obligation to pass it on to the future. Once one recognizes kuleana, actions are taken to fulfill that commitment. The kia’i (guardian) with kuleana invokes attention, respect, care, and kuleana for all things spiritual and physical.